A Wilderness Of Error Gets Lost in the Weeds

-

A Wilderness Of Error premieres Friday September 25th on FX.

A Wilderness Of Error premieres Friday September 25th on FX.The editor-in-chief of the daily newsletter Best Evidence, Sarah D. Bunting knows a thing or two about true crime. Her weekly column here on Primetimer is dedicated to all things true-crime TV.

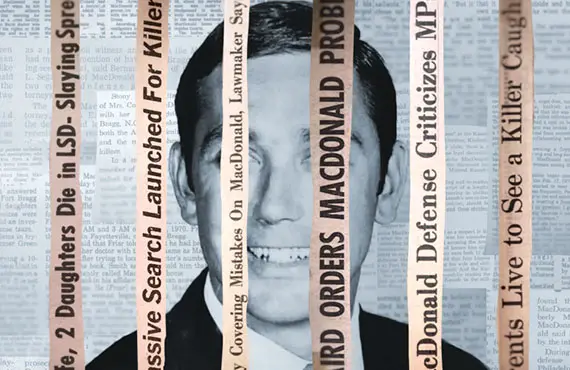

A Wilderness Of Error, the five-part docuseries premiering this week on FX, should be a slam-dunk. Focusing on who killed Dr. Jeffrey MacDonald's pregnant wife and two young daughters on a rainy night in February of 1970 -- a case that's fascinated me above almost all others for decades — Wilderness arrives with a titanically impressive pedigree. It's directed by the Oscar-nominated Marc Smerling, who produced The Jinx: The Life and Deaths of Robert Durst, Capturing The Friedmans, and Catfish in both documentary and series forms; and it's based on a book of the same name by Errol Morris, an Oscar-winner for The Fog Of War and the filmmaker behind 1988's The Thin Blue Line, which played a large role in reversing the wrongful conviction of Randall Dale Adams.

Alas, I can't quite recommend A Wilderness Of Error. Make no mistake: this is a gorgeously assembled work. The shot composition is thoughtful and compelling. Wilderness gets incredible access to everything, from never-before-seen photos and home movies to in terviews with just about every living person with a relationship to the case — Colette MacDonald's brother; notoriously controversial "witness" Helena Stoeckley's brothers; prosecutors and defense attorneys; MPs and crime-scene techs. And as I noted in my review of Errol Morris's book, I can't quibble with the thoroughness of his fact collection.

But Morris's book didn't do a great job marshalling all the available facts and re-examining them objectively — it ping-ponged between interview transcripts, profiles, and investigations of disputed evidence. In reading the book version, it struck me that the collaging Morris did would work better as a documentary, because Morris is less about introducing anyone to the facts, and more about presenting them selectively to convince people who think MacDonald is guilty (people like me) that he didn't commit the murders. But people who know the case (people like me) also know that Morris' book, and this limited series, leave out evidence and number of facts about MacDonald that are very damning. Wilderness won't lose me by arguing a viewpoint I don't agree with, but I don't think it's doing that; in fact, I honestly don't think it knows what it's arguing from scene to scene.

That is, unless what Morris is really trying to do is hang a light on the shifting nature of memory, perspective, and truth: that we can never know what happened, not least because the agendas of everyone on both sides — parents, prosecutors, investigators, informants — turned the facts of the case into a contest of who had the most cogent and believable narrative. Morris, who appears on camera periodically throughout Wilderness, has a cutesy bit at the end in which he admits that he too is an unreliable narrator in the MacDonald case, that he too has an agenda, and here again, in theory, I'm up for a thoughtful exercise on assumptions and how true-crime audiences' ideas get shaped by reporters and directors. Although I don't require my documentaries to be objective, I do like them to have an organizing principle, and it seems like Wilderness might use that unreliable-narrator button as a rationale for not picking a side.

There's also another ickier possibility, which is that Morris is on his own side — specifically, that he saw MacDonald's case as an opportunity to return to past activist glory, and free another wrongfully convicted victim. Marc Smerling rather pointedly starts the final episode of Wilderness with Morris greeting Randall Dale Adams upon his release from prison, and questions Morris directly on whether that was his motivation in digging into MacDonald's case. Morris is forthright in response — "Would I like to do it again? Yeah! I would!" — but it's a pretty bad look after almost five hours of not-entirely-good-faith arguments about the "unreliability" of the evidence against MacDonald.

At a time in American history when we're questioning many of the things that we used to take for granted about the criminal-justice system, including possibly biased coverage of it, these are important conversations to have — about transparency in reporting, about a judge's discretion, about the human instinct to simplify and label. Maybe Wilderness wants viewers to confront why we privilege certain sources and "experts" over others when it includes a talking-head interview with Christina Masewicz, who's chyroned as a "true crime fan"; why isn't she just as credible a commentator as prosecutor Jim Blackburn, since disbarred for fraud? But throwing a selection of information into a big heap and standing near it saying "See?" isn't the effective use of form and function that Smerling and Morris might think, and while Wilderness isn't a waste of time, Gene Weingarten's 2012 WaPo profile of prosecutor Brian Murtagh gets the same job done in a fraction of the time.

The first three episodes of A Wilderness of Error air on FX September 25th at 8:00 PM ET, with new episodes airing Friday nights through October..

Sarah D. Bunting co-founded Television Without Pity, and her work has appeared in Glamour and New York, and on MSNBC, NPR's Monkey See blog, MLB.com, and Yahoo!. Find her at her true-crime newsletter, Best Evidence, and on TV podcasts Extra Hot Great and Again With This.

TOPICS: A Wilderness of Error, FX, Errol Morris, Marc Smerling, True Crime

- Reenactments have become all the rage in true-crime docuseries

- A Wilderness of Error fails in its attempt to pull a "Jinx"

- FX's A Wilderness of Error is a new kind of true-crime documentary that will keep you on the edge of your seat

- FX unveils the trailer and premiere date for Errol Morris' A Wilderness of Error