Futurama Needed a Fanbase as Passionate as Its Creators to Survive

-

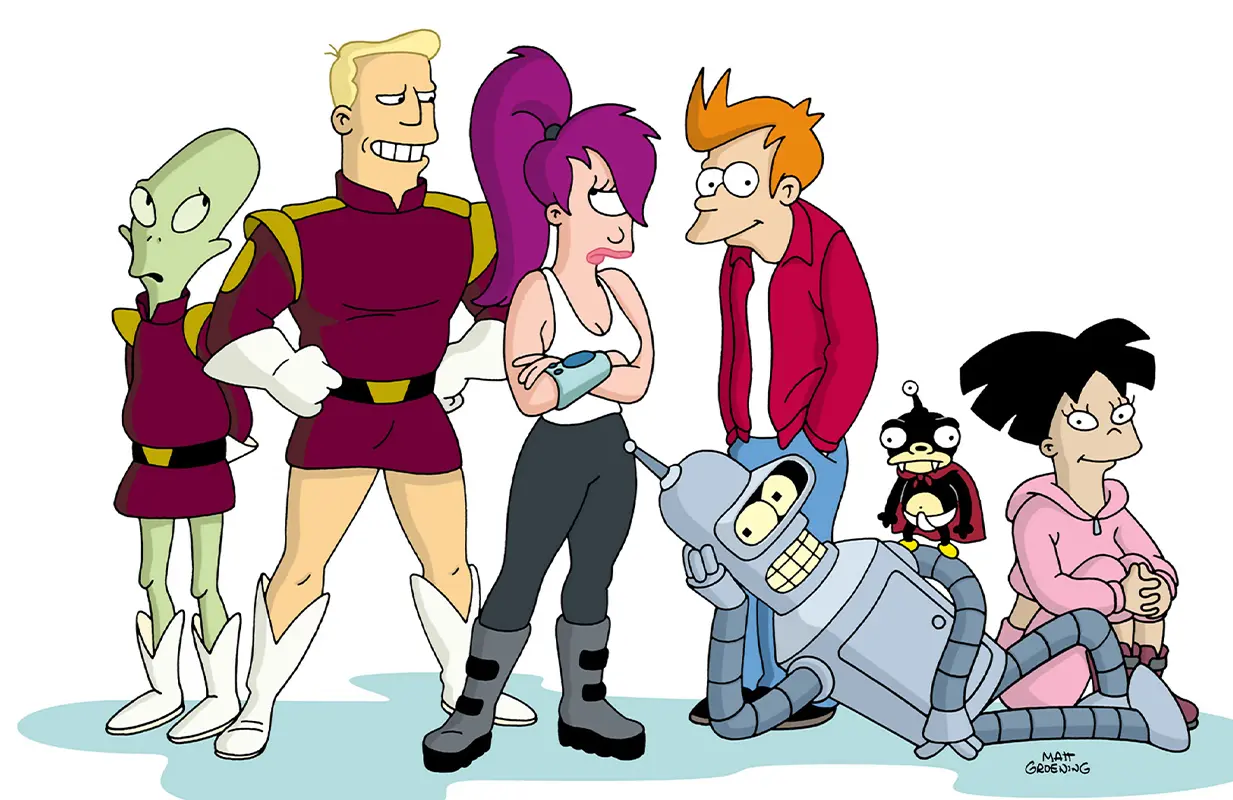

Futurama (Image: 20th Century Fox/Everett Collection)

Futurama (Image: 20th Century Fox/Everett Collection)When Futurama premiered on Fox in March 1999, it did so almost a decade after Matt Groening had broken open the gates of modern mainstream TV animation with The Simpsons. The intervening 10 years had seen more mature animated fare on the small screen, from the edgy Ren and Stimpy to the cult favorite The Critic. Though The Critic was created by two longtime Simpsons writers (and led to a moderately controversial crossover between the two), Futurama marked Groening’s first new series since The Simpsons.

Now that we’re a quarter-century removed from its premiere, you can draw some rough lines between the comedic style and character development of the two series, but the strengths of Futurama lie in something that The Simpsons deliberately never featured as its foundation: a hook-driven high concept that was both immensely appealing to eventual diehard fans, and yet not enough to draw in the same wide audience as the show about a town called Springfield.

In the first episode, “Space Pilot 3000,” Futurama wastes little time in establishing its high-concept premise: What if an average guy from the year 1999 inadvertently is cryogenically frozen and wakes up 1000 years later? Philip J. Fry (voiced by animation legend Billy West), an NYC pizza delivery guy whose girlfriend dumps him on New Year’s Eve 1999, realizes too late that his last delivery of the night was a prank call. Adding insult to injury, when Fry decides to ring in the new millennium at that prank location (an empty cryogenics lab), he literally slips and falls into an open cryogenic pod that is set to open in a thousand years. When it does, Fry is stunned to see what is now dubbed New New York City on the eve of the year 3000.

By the end of the pilot, Fry and his new friends — the beautiful purple-haired cyclops Leela (Katey Sagal) and the suicidal and vice-driven robot Bender (John DiMaggio) – work for Fry’s very elderly relative Dr. Farnsworth (West again) at his package delivery service Planet Express. The fish-out-of-water concept was a major focal point of the entire first season, as Fry gets a better understanding of how society operates in the year 3000 while also navigating a much more dangerous version of delivering packages than he ever experienced in the 20th century.

Though Futurama has never been able to boast the same widespread fandom that The Simpsons has, its success is almost more remarkable considering that it’s jumped from Fox to Comedy Central to Hulu (with a brief stop in the mid-2000s on Adult Swim, where syndicated reruns did so well that revivals became more realistic). And though Futurama hasn’t inspired theme-park lands like Matt Groening’s other show, its impact is such that a gag about global warming wound its way into An Inconvenient Truth, the Oscar-winning documentary from former Vice President Al Gore (whose daughter Kristin Gore was a writer on the show, and who was a recurring guest star as well).

The Futurama fanbase may be smaller, but its passion is undeniable, whether it’s in writers dinging the show for scientific inaccuracies (while acknowledging that The Simpsons often had very effective if cutting depictions of comic-book nerds offering such criticisms to artists), or in recent threats of boycotts. That latter outcry came when Hulu’s revival of Futurama meant the potential loss of DiMaggio as Bender due to a lower contract offer. As much as any revival is a sign of a network identifying a sense of love among fans, it’s just as true that these outcries can have an impact, because DiMaggio did end up returning as the lovably louche robot.

Whereas The Simpsons has successfully navigated through more than 30 years of stories and the eventual merger between Fox and Disney (the latter enabling them to make crossover short films featuring Disney characters), Futurama has always been a scrappier underdog that has to fight off bigger attackers. Part of that was established in the lengthy development process for the series; Groening himself said “It has been by far the worst experience of my grown-up life,” in reference to getting the show out of development and on the air. (It should be noted that he made this comment literally while promoting the series’s first season.)

The issue was less his work with co-creator David X. Cohen and more about getting the new regime of Fox executives to sign off on a series that looked somewhat like The Simpsons while being much darker in execution. “In one respect, I will take full blame for the show if it tanks, because I resisted every single bit of interference,” Groening says later on in that archived interview. Certainly Futurama is a bleaker show from the outset. For one example, Bender’s suicidal nature is not exactly existential: Fry’s first encounter with Bender is at a literal Suicide Booth, and it’s only through quick thinking that Fry escapes with his life. (The show eventually lets up on Bender’s suicidal ideation, but as an introduction, it’s fairly bleak.)

By setting the series so far into the future, the writers and animators were able to make Futurama feel only somewhat dated — there’s no way for any of us to know exactly how little or how much any of its futuristic vision will ever come true. One aspect that is fairly dated and feels like a Simpsons riff perhaps best left unexplored is the idea that many famous 20th-century-era celebrities’ heads remain alive in jars. Itself a gag on the famous myth that Walt Disney was cryogenically frozen, the bit is introduced in the pilot courtesy of a cameo from Leonard Nimoy as well as the first of many recurring appearances by the still-living head of former President Richard Nixon. Some of the novelty of this gag has long since worn off, whether through appearances in later episodes by celebs like Pamela Anderson or the recurring appearances of former Vice President Al Gore.

What made Futurama work at its best — and though the series’s lifespan has seen it jump from Comedy Central to Hulu over the years, its best episodes are primarily those that Fox aired in its original four-season run — was its blend of recognizably retro takes on futuristic ideas and a more modernist and anarchic take on the same concepts. Each episode’s opening title sequence begins with the Planet Express ship sailing through New New York City and then crashing into a large screen displaying a random clip from a 1930s-era piece of animation, as a kind of micro version of the blend of old-fashioned and cutting-edge within the series itself. Fry’s discovery of what New New York City is like feels as much like something out of an old-school World’s Fair — flying cars! Talking robots! Underwater housing! — as it is weird and intriguing and baffling.

Fox made it harder on the show almost from the get-go. While the series pilot aired right after The Simpsons, Futurama soon was bounced around the network’s schedule until it eventually wound up airing at 7:00 P.M. on Sundays. That time slot all but guaranteed delays due to football overruns on Fox, so that when Futurama’s production order ended after its fourth season, the network simply stopped ordering new episodes.

And yet, before shows like Arrested Development got a new life on streaming platforms like Netflix, Futurama survived due to its popularity in syndication and eventually got to have a second life via direct-to-DVD movies and additional episode orders on Comedy Central, and then a third life on Hulu. (The episode order that Hulu has extended will last the show into at least 2026.)

As difficult as the show’s development was, Futurama burst out of the gate with a solid sense of character and place. In hindsight, it’s both easy to wonder why Fox executives wouldn’t have instantly paired the show with The Simpsons and easy to understand why they were leery. On one hand, two shows from the same animation impresario airing back-to-back seems pretty straightforward, especially since the character design on Futurama wasn’t so far off from the world of Homer, Marge, and Bart. (You could reductively pair them up with Bender, Leela, and Fry, respectively.) But Fox didn’t hand over the Animation Domination block to Matt Groening.

Instead, that honor went to Seth MacFarlane, the creator of the other animated show Fox premiered in the early days of 1999. After its post-Super Bowl premiere, Family Guy wound up airing right after The Simpsons in April of the same year, kicking Futurama off Sunday nights.Though it, too, would only get a second life thanks to syndication, Family Guy was always an easier sell for Fox. Futurama may have been weirder than Groening’s other work, but that oddness is a hallmark of its charms, which still remain 25 years later.

Josh Spiegel is a writer and critic who lives in Phoenix with his wife, two sons, and far too many cats. Follow him on Bluesky at @mousterpiece.

TOPICS: Futurama, FOX, Family Guy, The Simpsons, Matt Groening

- Anthony Mackie's Twisted Metal Puts a Comedic Spin on the Hit Video Game

- Futurama's John DiMaggio Says He 'Didn't Get More Money' to Return for Hulu Revival

- John DiMaggio joins Hulu's Futurama revival: "I’M BACK, BABY!"

- John DiMaggio speaks out on his Futurama contract negotiations: "It's about self-respect"