Scouts Honor Eschews Neutrality to Paint a Blistering Portrait of the Boy Scouts of America

-

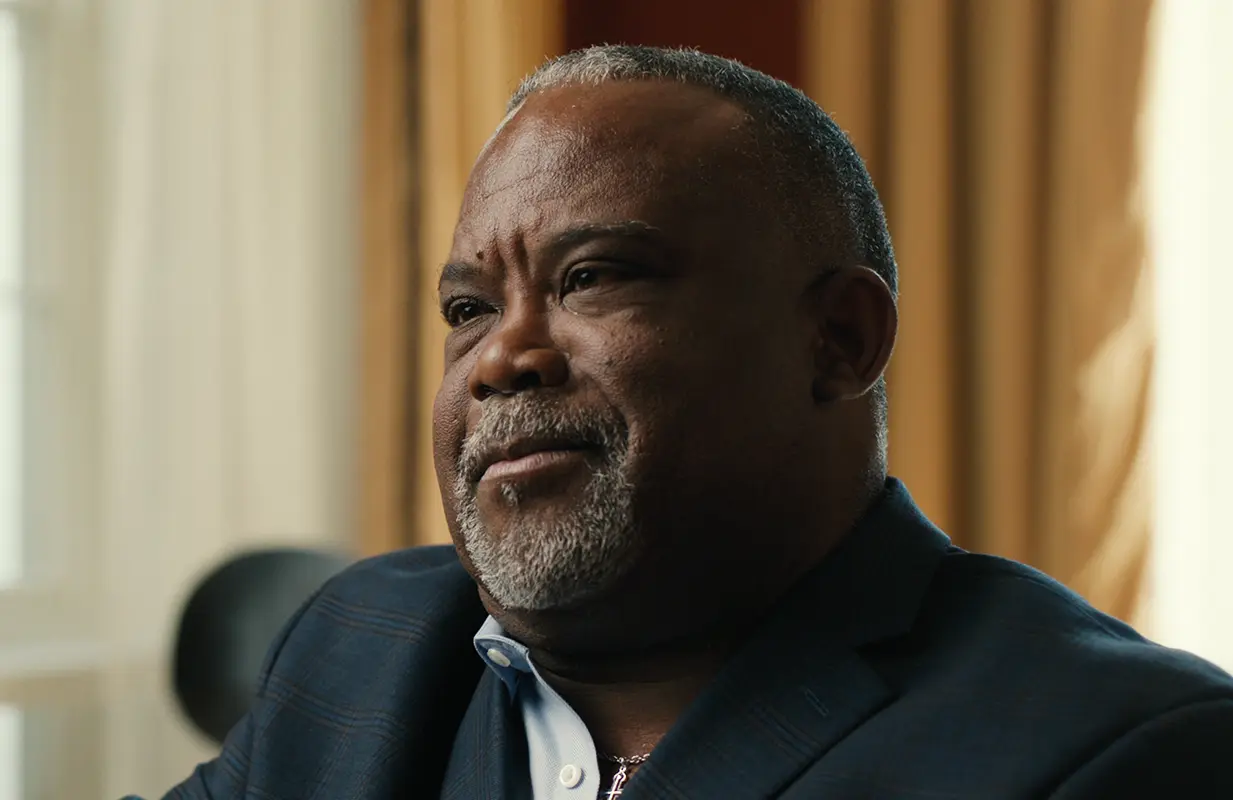

Michael Johnson, former youth protection officer for the Boy Scouts of America. (Photo: Netflix)

Michael Johnson, former youth protection officer for the Boy Scouts of America. (Photo: Netflix)[Editor's Note: This post contains references to sexual assault and child abuse.]

In a sea of documentaries unwilling to ask difficult questions or hold their subjects accountable, Scouts Honor: The Secret Files of the Boy Scouts of America stands out. Director Brian Knappenberger, who previously partnered with Netflix on The Trials of Gabriel Fernandez, eschews the fly-on-the-wall approach and takes it upon himself to get answers about the epidemic of sexual abuse within the youth organization. Though Knappenberger's voice doesn't guide the film — he leaves that to courageous survivors, many of whom speak out about their experiences for the first time — he understands that doing their story justice requires more than just being a neutral observer. It also means putting their trauma, and that of the 82,000 victims who have come forward with allegations in recent years, into context by examining the structures that enabled abuse inside the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) and allowed it to go unchecked for decades.

Scouts Honor takes a methodical approach to fulfilling this responsibility. The first half of the documentary places powerful testimony from survivors alongside information found in the Boy Scouts' confidential files, or the "Perversion Files," as they were also referred to by the organization. As journalist Patrick Boyle, who publicized the contents of the documents in 1994, explains, the files reveal the BSA was aware of abusers within their ranks and kept it quiet to maintain their wholesome image. In some cases, abusive Scout leaders — including Thomas J. Hacker, who molested hundreds of boys and is considered one of the country's most prolific predators — were "banned" in one community, only to move to another city and continue preying on children. "This organization was built in a way that molesters could get in, abuse kids, and get away with it," says Boyle.

The culture of silence is so baked into the Boy Scouts' DNA that it remains an intractable problem to this day. Knappenberger speaks at length with former youth protection officer Michael Johnson, who was brought in to address the scourge of child sexual abuse in 2010 but says he was kneecapped at every turn. He recalls receiving immediate pushback when he suggested requiring Scoutmasters and volunteers to submit a valid government ID, with higher-ups citing the great "inconvenience and cost" of the effort.

Johnson also claims Steven McGowan, who served as the BSA's general counsel from 2013 to 2022, discouraged him from reporting allegations because "the law doesn't mandate" such reporting "unless there's reasonable suspicion that there's sexual abuse." McGowan attempts to refute Johnson's characterization of their conversation by stating that children are told to report everything to "a trusted adult," but Knappenberger forces him to admit that the organization's training doesn't specifically encourage Scouts to seek out law enforcement. That policy is troublesome in and of itself, explains Johnson, as, "The perpetrator who's sexually abusing the youth or sexually harassing and bothering them is typically what was formerly a 'trusted adult.'" Instead, he proposed establishing a phone or text hotline through which children could file reports directly, but again, he was met with resistance. "When I took that proposal to Steve McGowan and then-vice president John Mosby, it was not, 'No,' but, 'Hell, no. We just want kids reporting to their trusted adults, the Scoutmasters,'" Johnson remembers.

But while Scouts Honor serves as a comprehensive takedown of the BSA, Knappenberger doesn't stop at the organization itself. In the second half of the film, he zooms out to explore the connection between the BSA and the Catholic and Mormon Churches. The religious groups were hugely influential within the organization: Catholic and Mormon leaders sat on the board of directors, adopted Scouting as their "youth ministry," and were among its biggest donors. As a result, the Scouts bent to their whims — especially as it related to gay members. In 1978, the BSA, spurred on by homophobic religious leaders holding the purse strings, banned openly gay Scoutmasters and employees, believing it "would end all these pedophile cases that were springing up," says Randall Hoenig, former executive director of the Wichita Falls, Texas chapter. Johnson backs up this point, claiming he was told by a vice president-level executive that "homosexuals are pedophiles, and that's our primary problem in Boy Scouts with youth protection."

Obviously, this is false and rooted in homophobia — as the documentary's talking heads explain — but the Scouts were so committed to the policy that they took it all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of the organization in the 2000 Boy Scouts of America v. Dale decision. It wasn't until 2015 that the BSA lifted the ban, though it shifted the burden to local chapters and individual troops by allowing them to "continue to choose adult leaders whose beliefs are consistent with their own."

Knappenberger's decision to emphasize the external forces at play leads to one of the documentary's most damning sequences. After exposing the close tie between the Scouts and religious organizations, the director asks McGowan directly about whether the belief that "homosexuality was equated with pedophilia" was common among top brass. McGowan attempts to sidestep the question, but Knappenberger refuses to let him off the hook. His fumbling answers — it's a lot of "I can't answer that" and "I wasn't there" — and attempt to shift the blame make his effort at damage control all the more transparent, especially when contrasted with the assuredness of Johnson's remarks. Johnson's interview, which is intercut with McGowan's, serves as a fact check on a man who's already been established as a subjective narrator. McGowan can claim "there was no pressure being exerted on us" to keep the gay ban in place until he's blue in the face, but it ultimately means nothing when placed next to Johnson's recollection of a conversation with chief financial officer Jim Terry, who allegedly told him, "The Mormons are sacrosanct."

The director's "follow the money approach" extends to the more recent developments in the scandal, including the BSA's Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing in February 2020, which came in response to 275 abuse lawsuits and up to 1,400 additional claims. (That number grew to 82,000 over the course of the proceedings.) Legal and financial experts explain that bankruptcy proceedings are structured to "protect the debtor," but in this case, that means an institution that willfully neglected its members and enabled abusers lives to see another day. "No one was thinking about child sex abuse when Chapter 11 was put into place ... It's a legal proceeding that turns the victims into collateral damage, just like they were as a kid," says Marci Hamilton, CEO of Child USA. "Bankruptcy is constructed for the powerful. And the powerful win."

Hamilton's matter-of-fact statement gets at the unfortunate truth of this case. The reality is that the vast majority of these survivors will not receive any compensation from the Boy Scouts — and if McGowan's gross attempt to downplay the number of victims ("82,000 over what period of time? We don't even know that's the number") and suggest that abuse happens everywhere is any indication, they won't be getting a real apology from the offending organization. There also has yet to be a thorough investigation into the BSA on a Congressional, federal, or state level, even though it's been decades since the "Perversion Files" were first made public and years since the organization declared bankruptcy. As our institutions continue to fail these survivors, Scouts Honor is likely the closest they will get to anything approximating justice. And with Johnson claiming that "the organization is still not safe for boys and girls," Knappenberger's blistering exposé may be the only way the next generation of Scouts remain protected from further abuse.

Scouts Honor: The Secret Files of the Boy Scouts of America is streaming on Netflix.

Claire Spellberg Lustig is the Senior Editor at Primetimer and a scholar of The View. Follow her on Twitter at @c_spellberg.

TOPICS: Scouts Honor: The Secret Files of the Boy Scouts of America, Netflix, Brian Knappenberger