Antihero TV Reached Its Pinnacle in Deadwood

-

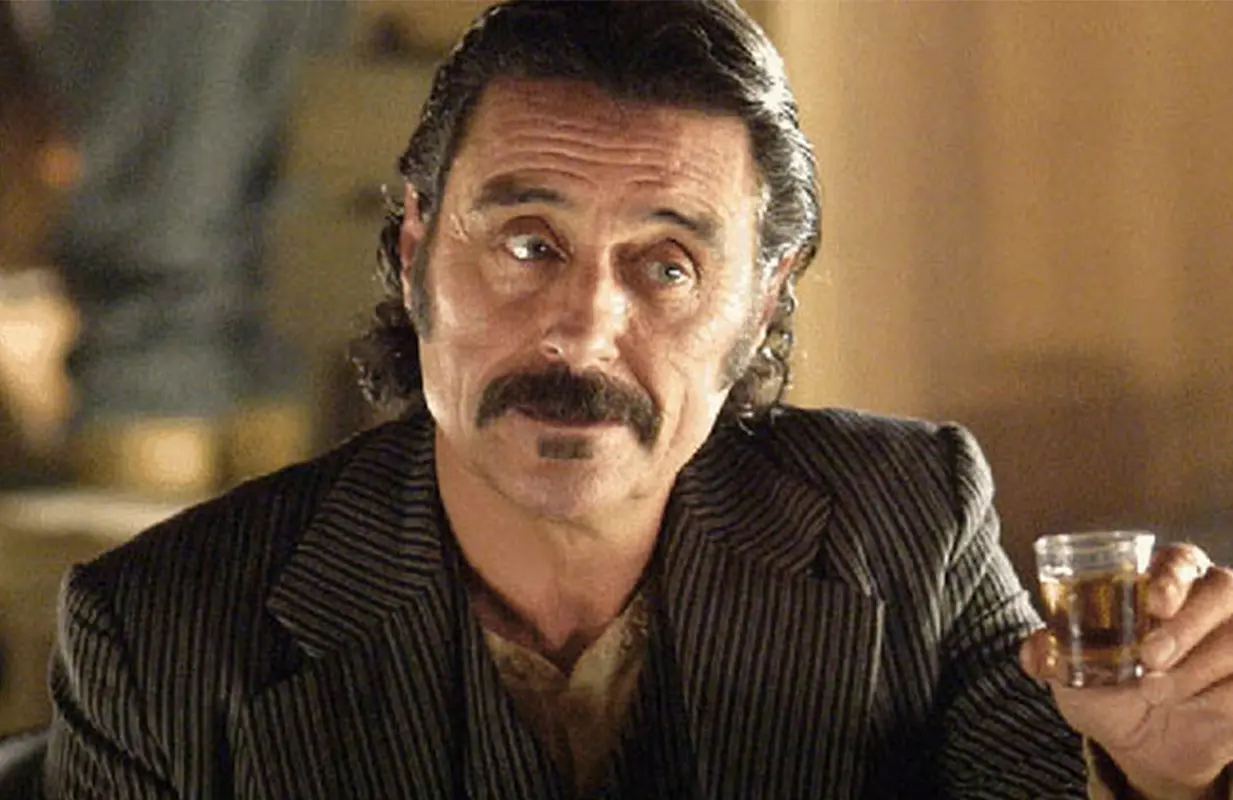

Ian McShane in Deadwood (Photo: HBO)

Ian McShane in Deadwood (Photo: HBO)January 10, 1999 marked the premiere of the HBO drama series The Sopranos, which took the high concept of a detailed glimpse into the modern mafia and ran with it, offering audiences a very adult, complex, and mature show that far surpassed its initial hook. But while The Sopranos kicked off the era of antihero TV, it took a few more years for other series to truly grab the baton from Tony Soprano. Within the world of HBO, though some other dramas would peer into other worlds of Americana, from the carnies of Carnivàle to the disaffected funeral-home employees of Six Feet Under, the most memorable and arguably the best of antihero TV arrived on TV in March of 2004, in the form of Deadwood.

For all of the profanely beautiful Shakespearean dialogue crafted by series creator David Milch, he cut to the very heart of antihero TV without even intending it in the Deadwood pilot, directed by genre craftsman Walter Hill. Among the many Old West characters who have descended upon the Black Hills of South Dakota in 1876, one we meet in the opener is bearded miner Ellsworth (Jim Beaver). Ellsworth is a secondary presence in the pilot, first seen chatting at the Gem Saloon, overseen by Al Swearengen (Ian McShane).

If you’re TV literate enough, you might take a quick look at the images of the Gem Saloon and recall the opening title sequence of Cheers, with its illustrations of bartenders and patrons enjoying each other’s company and some booze. At first glance, Swearengen looks much like the barkeeps in those paintings, well-dressed and mustachioed and avuncular. He nods and smiles as Ellsworth crows about his relative largesse due to a “workin’ fucking gold claim” in those gold-rich hills. Al even promises Ellsworth that no one will try to rob him of said gold while inside the Gem, to which Ellsworth cheerfully replies, “Goddamn it, Swearengen, I don’t trust you as far as I can throw you, but I enjoy the way you lie.”

Milch hits the nail on the head with that line. It’s not only a solid bit of foreshadowing within the series itself, as it quickly becomes evident that Al Swearengen is an Old West version of a Mob boss trying to control the goings-on in Deadwood from behind the scenes and using violence as often as needed. Al has no shame in stooping to murder, and although Deadwood is lawless at the start, he quickly butts heads against its eventual sheriff, ex-U.S. Marshal Seth Bullock (Timothy Olyphant). Al treats the prostitutes at the Gem fairly roughly, including Trixie (Paula Malcomson), whose own violent streak is quickly revealed in the pilot. Al’s also intensely greedy, manipulating a foppish New Yorker (Timothy Omundson) and eventually having him killed so he can lay claim to the outsider’s gold. Yet Swearengen ought to be placed alongside characters like Tony Soprano, Vic Mackey, and Walter White, as another immensely compelling and yet often immensely awful person.

Part of what makes Deadwoodd so special is its surprisingly deep humane streak. McShane — who delivered the performance of a lifetime as Al — is immediately fascinating to watch as a bundle of contradictions who can be as cruel as he can be kind, or even somewhat pitiable. One of the first season’s later episodes concludes with Al giving a monologue that allows us to learn briefly about his childhood. Of course, Deadwood being Deadwood (a show that was very, very proud of having no content restrictions on HBO), Al is sharing these pieces of his past while receiving oral sex from one of his prostitutes. “I don’t look f*cking backwards, I do what I have to go and go on,” he says partially to no one in particular before revealing that his mother dropped him off at an orphanage run by a whorehouse matron. As twisted as it is, Al gets more depth here than you might otherwise expect (or perhaps even demand) considering his largely nasty behavior.

Even in the first-season finale, “Sold Under Sin,” Al reveals hidden depths of kindness. Just as Deadwood could be boisterous and very funny, or intense or scary, its ability to mine heartbreak was equally remarkable. Anyone who knows the show well knows the tragedy of Reverend Smith (Raymond McKinnon), a kindly if somewhat obtuse preacher attempting to spread the word of God in Deadwood. Throughout most of Season 1, his sermons fall on deaf ears even though Seth and his hardware-store partner Sol Star (John Hawkes) are at least willing to spend time around him. But over the course of the season, Smith begins having strange episodes that are inspired by a fatal brain tumor.

In “Sold Under Sin,” Al has to take it upon himself to do the hard thing that no one else is willing to do: perform a mercy killing on the Reverend. The monologue linked above, from the penultimate episode, teases at Al’s weighty awareness that “he’s gonna die sooner or later” and that it’s up to him to enact the death. “You want to be a road agent? Deal out death when called upon?” he hisses at one of the saloon employees, Johnny (Sean Bridgers), before walking him through exactly how to suffocate a man to death. It’s a heartbreaking scene instead of a horrifying one — as sad as the Reverend’s suffering is, Al’s doing the only good thing possible simply to end the man’s physical misery. And in depicting this mercy killing, Al acts as a mirror version of the seemingly upright Seth Bullock, who performs a mercy killing of his own in the opening scene of the show, literally helping a man hang to death instead of being brutally shot by drunken would-be cowboys.

Milch used Deadwood as much more than a way to create an R-rated Western years before Quentin Tarantino would do so with Django Unchained. It’s easy to remember that Deadwood was the show with an incredible amount of profanity (both for its era and for the year of our Lord 2024), but the series essentially used the trappings of the R-rated TV drama in its early years to make a larger commentary not only on the twisted humanity of a man like Al Swearengen, but on the equally strange yet livable man-made community of Deadwood.

The end of the show’s first season brings with it more signs of recognizable civilization. Bullock, trying so hard to avoid his past as a marshal, agrees to be the town’s sheriff, leading to more struggles with Al and the more lawless members of Deadwood in the second season. By the show’s third and final season, the presence of the U.S. government is impossible to avoid and the powerful developer George Hearst (Gerald McRaney) reveals himself to be even crueler and more violent than Al, and with a hell of a lot more money behind him.

Even if Deadwood initially presented a world where a man could be shot dead in the middle of a muddy would-be road, there’s something more insidious about the onslaught of the modern world Hearst represents in comparison. Over the course of those three seasons (as well as in the very good follow-up film from 2019), Al Swearengen and Seth Bullock occupied opposing roles, but each was multi-layered and compelling, instead of just being clear-cut cases of evil or good men. Hearst, on the other hand, is depicted as close to pure evil, less an antihero than a true, hissable villain.

The series finale of Deadwood, which aired in the summer of 2006, is named after the final line of dialogue, which is fittingly uttered by Al himself. “Tell Him Something Pretty” is the episode, and the final line is Al muttering to himself, “Wants me to tell him something pretty.” Al is, at the moment, scrubbing off blood from the floor of his office and has to briefly placate Johnny. (The ins and outs of the plot in this moment would be too much to dive into here, but the short version is that Al had to kill one of his prostitutes to ensure that Hearst would leave town.) Though describing what Al has done may yet prove him to be a heartless cur, the glimpse we get from the dialogue right before the last line is as revelatory as anything else. When Johnny asks if the dead woman suffered, Al curtly says, “I was gentle as I was able, and that’s the last we’ll fucking speak of it.”

Al’s worldliness is such that he can only somewhat fathom why Johnny would care so much (and knows he wouldn’t care himself), but as horrific as his actions can be, the soul of the man became more and more visible over the series’s tragically short three-season run. (Though some people do enjoy Milch’s follow-up series John From Cincinnati, which shared a few cast members, it sure would’ve been nice to get a true fourth season of this series instead.)

Deadwood has, because of that shorter run, maybe not had quite the same impact on the world of TV as Breaking Bad or even the remarkable Mad Men did, both arriving later in the era of the antihero. But Deadwood is the apotheosis of antihero TV, giving us a peek into a world as strange and fascinating as that of Westeros in Game of Thrones, allowing us to sympathize with monsters, à la Walter White or Tony Soprano, and offering a depth of humanity rarely seen on the small screen, especially in such R-rated trappings. 20 years later, Deadwood still remains the pinnacle of the era.

Josh Spiegel is a writer and critic who lives in Phoenix with his wife, two sons, and far too many cats. Follow him on Bluesky at @mousterpiece.

TOPICS: Deadwood, HBO, David Milch, Ian McShane, Ray McKinnon, Timothy Olyphant