Daisy Jones & the Six Ultimately Betrays the Novel’s Heart

-

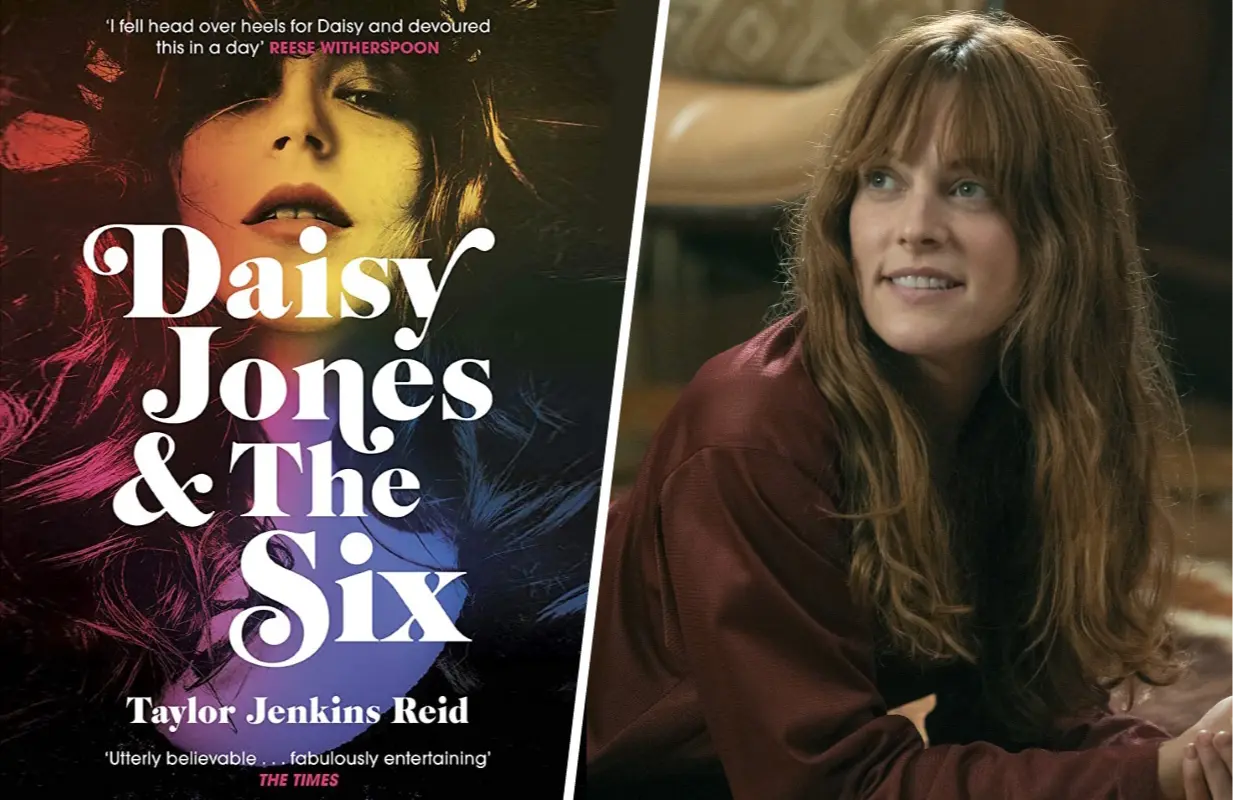

The cover of Daisy Jones & the Six, plus Riley Keough as Daisy (Photo of Keough: Lacey Terrell/Prime Video)

The cover of Daisy Jones & the Six, plus Riley Keough as Daisy (Photo of Keough: Lacey Terrell/Prime Video)[Editor’s Note: This post includes spoilers for the final episodes of Daisy Jones and the Six.]

They keep Chuck alive, then they make fun of him. Plot-wise, that’s a fairly small way that Scott Neustadter and Michael H. Weber alter Daisy Jones & the Six, the Taylor Jenkins Reid novel they’ve adapted into a Prime Video limited series. Chuck isn’t in the story very long. He doesn’t even meet Daisy Jones, the singer-songwriter at the center of this saga about a ‘70s rock band. But as minor as he is, he still epitomizes the failure of imagination that makes the show such a disheartening step down from its source material.

In both the novel and the show, Chuck is originally a member of the band that Billy Dunne and his brother Graham form with their teenage friends. In the book, he gets drafted, then dies in the Vietnam War. In the series, whose final episodes stream March 24, he quits because he wants a stable life. He returns later, proudly announcing he’s a dentist and teasing his buddies for struggling to make it. The gag is that he doesn’t realize how much money they’re making, now that they’ve joined forces with Daisy (Riley Keough) and begun conquering the world. The series even uses one of its signature flash-forwards to show an older Chuck (Jack Romano) tipping his head back in embarrassment. Instead of representing the horror of the war and the holes that dead soldiers leave in people’s lives, he’s just a suburban schmuck who doesn’t know rock gods when he sees them. The poignant ache in Reid’s writing is traded for a reductive bit.

This happens over and over. When the TV versions of Billy and Graham (Sam Claflin and Will Harrison) see their deadbeat dad at a concert, the old man insults them, then Billy punches him in the face. It’s a quick way to establish Billy’s inner demons while repeating a familiar trope about young men and their fathers. Compare that to the novel, in which Mr. Dunne doesn’t recognize his sons at all. Instead of hitting something, Billy absorbs the pain of being invisible. That sets up his evolution into a hedonist and, finally, a man who clings to those who truly see him. Those textures are missing from the series, where Billy is a more typical tortured artist. He rarely balances his egotism, preening, or wandering eye with the type of soul-searching that makes him compelling on the page.

But at least he’s still a forceful character, fighting to control his destiny. The screen adaptation makes Daisy almost completely reactive. Even though she’s still a gifted artist, her choices are mostly driven by men, and especially Billy. Whether she’s writing about him, marrying someone else in spite of him, or taking drugs to forget him, he dominates her behavior. And yes, in the book Daisy and Billy also have a tortured, untenable love. Daisy’s heartache is a large part of the narrative. But in Reid’s book, she has an entire career before she joins Billy’s band The Six — she writes songs and releases her own album. She has lengthy monologues about her passion for her art. Her doomed desire doesn’t make up her entire life.

It’s Billy’s wife Camila, however, that the series most deeply betrays. She might be Reid’s most surprising creation: a woman who can see the good in Billy and Daisy both, even when they’re on the verge of tearing her family apart. In a moving scene near the end of the novel, she tells Daisy she needs to leave the band, for her own good as well as everyone else’s. “Daisy, I don’t know you very well,” Camila says, “but I know you have a great heart and you’re a good person… When I see you, I see an incredible writer — who suffers from the very thing that the man I love suffers from. The two of you think you’re lost souls, but you’re what everybody is looking for.”

Her kindness and maturity ripple through the final chapters, and they help make Reid’s novel about something bigger than rock stars in heat. Camila helps Daisy Jones and the Six become a tale of transformative generosity.

In the corresponding scene in the series, Camila (Camila Morrone) hisses that Daisy is a disaster and that she and Billy deserve each other, for all they’ve put her through. It’s a catfight, not a turning point, and it cheapens Camila’s heart. So does an earlier moment, when her anger over Billy’s feelings for Daisy pushes her to sleep with one of Billy’s bandmates. The original Camila might counsel her screen counterpart, but she would never behave like her.

The show does end with Camila and Billy getting back together. Daisy does move on to a healthier life. And when it’s revealed that Billy and Camila’s daughter has been interviewing everyone in the flashforwards, there is a glimmer of the compassion that Reid so beautifully wrote. But it’s just a glimmer. A show this dull can never really shine.

Daisy Jones & the Six is now streaming on Prime Video. Join the discussion about the show in our forums.

Mark Blankenship has been writing about arts and culture for twenty years, with bylines in The New York Times, Variety, Vulture, Fortune, and many others. You can hear him on the pop music podcast Mark and Sarah Talk About Songs.

TOPICS: Daisy Jones & The Six, Daisy Jones and the Six, Camila Morrone, Michael H. Weber, Riley Keough, Sam Claflin, Scott Neustadter, Taylor Jenkins Reid