Netflix's Mataviejitas Murders Asks Where the Justice Is in the Case of Mexico's First Serial Killer

-

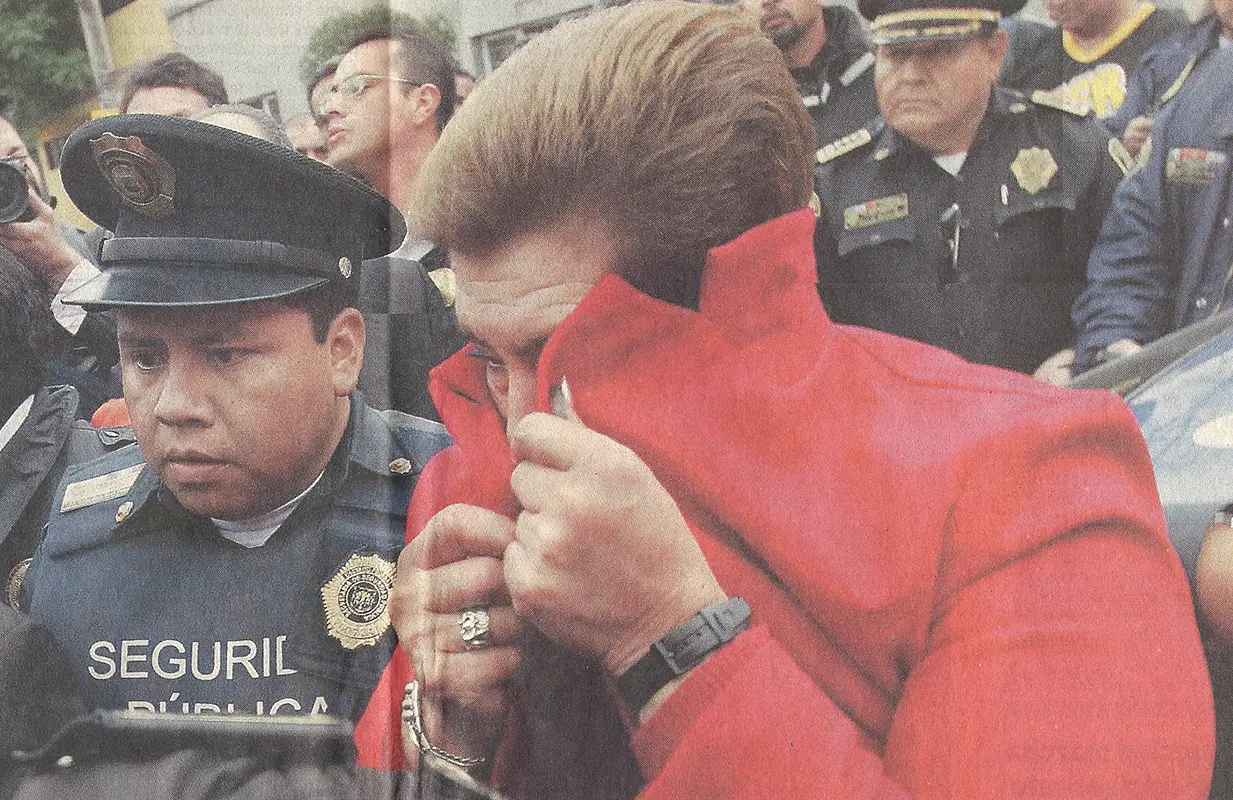

Juana Barraza, the woman dubbed La Mataviejitas by the Mexican media. (Photo: Netflix)

Juana Barraza, the woman dubbed La Mataviejitas by the Mexican media. (Photo: Netflix)Netflix's The Lady of Silence: The Mataviejitas Murders, a Spanish-language documentary about Mexico's first serial killer, ends with a conviction: In 2008, Juana Barraza was sentenced to 759 years in prison for the murders of 16 elderly women in Mexico City. From the late 1990s to 2003, Barraza, disguised as a nurse involved in a social welfare program, gained entry to the homes of her victims and strangled them with common household items. Witnesses saw Barraza entering or leaving some of the crime scenes, resulting in composite sketches of the person dubbed La Mataviejitas, or "The Little Old Lady Killer," but even as the violence intensified — she's believed to be responsible for over 40 murders — Barraza managed to evade capture until 2006, when she was arrested fleeing a victim's home.

While authorities successfully identified the killer, there's hardly any justice to be found in this case. Documentary director María José Cuevas is careful not to get tripped up by the salacious nature of the murders, which dominated the media at the time and left a mark on Mexican pop culture. Instead, Cuevas casts a skeptical eye on the investigation as she shines a light on the deceptive and discriminatory tactics employed by a police force wholly out of its depth.

Much like the investigation itself, The Lady of Silence moves in fits and starts as it sets up Barraza's arrest (after all, it took eight years for her to be identified as La Mataviejitas). The first half of the film centers on the many wrong turns taken by Mexican authorities, who were unfamiliar with serial killers and proper crime scene preservation, as deputy prosecutor Renato Sales freely admits. As the victim count increased, police became desperate to find the killer, but with so little hard evidence to work with — and conflicting witness statements about the perpetrator's appearance — they began pointing fingers. In early 2004, Matilde Sánchez Gallegos, a nurse at the Institute for Social Security and Services for State Workers, was arrested because she matched the physical description of the murderer; she was later released due to a lack of evidence, but only after she was publicly named as La Mataviejitas and her face was splashed all over the news.

A few months later, another woman, Araceli Vázquez, was arrested for a series of robberies, and she was soon linked to several of the murders, with prosecutors citing her effort to "deceive" elderly people "with the promise of financial aid cards" and a fingerprint left on a glass in one of the victim's homes as evidence. At the time, suspects were publicly introduced when they were brought in for questioning, creating an environment in which the accused were "exposed to whatever the police wanted to do and say," explains journalist Claudia Bolaños. In Vázquez's case, that meant being told to wear a white nurse's coat and wig, which were believed to be worn by the serial killer to disguise her identity, as she fielded questions from a press corps hungry for a story. Vázquez, who has been in prison for 19 years, denied any involvement in the killings, but prosecutors held firm on the charges, even when it became clear that the killer was still at large — and even after Barraza was convicted.

It wasn't just individuals who were targeted by investigators. Witnesses reported that La Mataviejitas was broad-shouldered with large hands, leading some to suspect that the perpetrator could be a man disguised as a woman. With that "theory" in mind, the police launched a sweep of the transgender sex worker community, and 80 to 100 people were arrested without probable cause. Former sex workers claim they were abused and tear-gassed, with one, Orquídea, remembering being told by officers, "Don't look at me. You are so f*cked." They were taken to the police station, fingerprinted, and evaluated for a resemblance to the composite sketches of the serial killer; one subject, Alma Delia, recalls detectives identified them as the criminal "simply because of [their] physique." Adds Orquídea, "They violated all our rights. They trampled us and all that."

Cuevas gives Mexico City attorney general Bernardo Bátiz, who became a well-known figure during the investigation, and homicide prosecutor Guillermo Zayas a chance to respond, but they're hardly remorseful. Bátiz denies ordering a raid at all, and he shifts blame to local police precincts, which he suggests "did something on their own" to "confront on the streets what [he] only saw from far away in [his] office." For his part, Zayas doesn't address the allegations of physical abuse or coercion; he claims the sex workers were "only" brought in "to see if the fingerprints matched," but "there were no bookings" (a statement that directly contradicts the sex workers' accounts). "We apologized," Zayas says, with little emotion in his voice. "But we had to investigate. We were working on a very serious, very severe case."

As the documentary introduces Barraza and her career as a professional wrestler (she was known as La Dama del Silencio, or "The Lady of Silence," hence the title), its focus shifts away from the many people wrongly accused of being La Mataviejitas, but Cuevas returns to Vázquez's story in the final 20 minutes. In an emotional interview, Vázquez maintains her innocence and insists she's been unfairly blamed for Barraza's crimes. The evidence presented in this sequence reinforces her claim: Vázquez doesn't match the suspect's profile, and the daughter of victim Gloria Enedina Rizo reveals she was told by police that the fingerprint supposedly pointing to Vázquez's involvement actually matches Barraza. "I assumed that if they found the other woman, then Araceli would be released right away," says Verónica Rizo. "That did not happen."

When Cuevas presses Bátiz and Sales, the prosecutors insist they "don't remember" Vázquez and offer platitudes about the "unfortunate" reality of her situation. As Sales fumbles over his response, speaking in generalities about the "mechanisms in place to solve" potential "judicial errors," it becomes clear that correcting this particular miscarriage of justice is not a top priority. "One should be able to acknowledge that an error was made," he says, without ever once admitting that in the case of Araceli Vázquez (whom Sales does not mention by name), that's exactly what seems to have happened.

Prosecutors involved in Vázquez's case may not be concerned with righting this wrong, but The Lady of Silence keeps the hope for justice alive. Cuevas makes such a compelling argument for Vázquez's innocence — just as she does for Jorge Mario Tablas Silva, a man sentenced to nearly 70 years in prison for crimes later linked to Barraza — that viewers are likely to come away with righteous indignation on her behalf. In an ideal world, the documentary will lead to her exoneration, as well as reparations for those who were unfairly persecuted by investigators grasping at straws to find La Mataviejitas.

The Lady of Silence: The Mataviejitas Murders is now streaming on Netflix.

Claire Spellberg Lustig is the Senior Editor at Primetimer and a scholar of The View. Follow her on Twitter at @c_spellberg.

TOPICS: The Lady of Silence: The Mataviejitas Murders, Netflix, Juana Barraza, María José Cuevas, True Crime