Telemarketers Is a Testament to the Power of Asking Questions

-

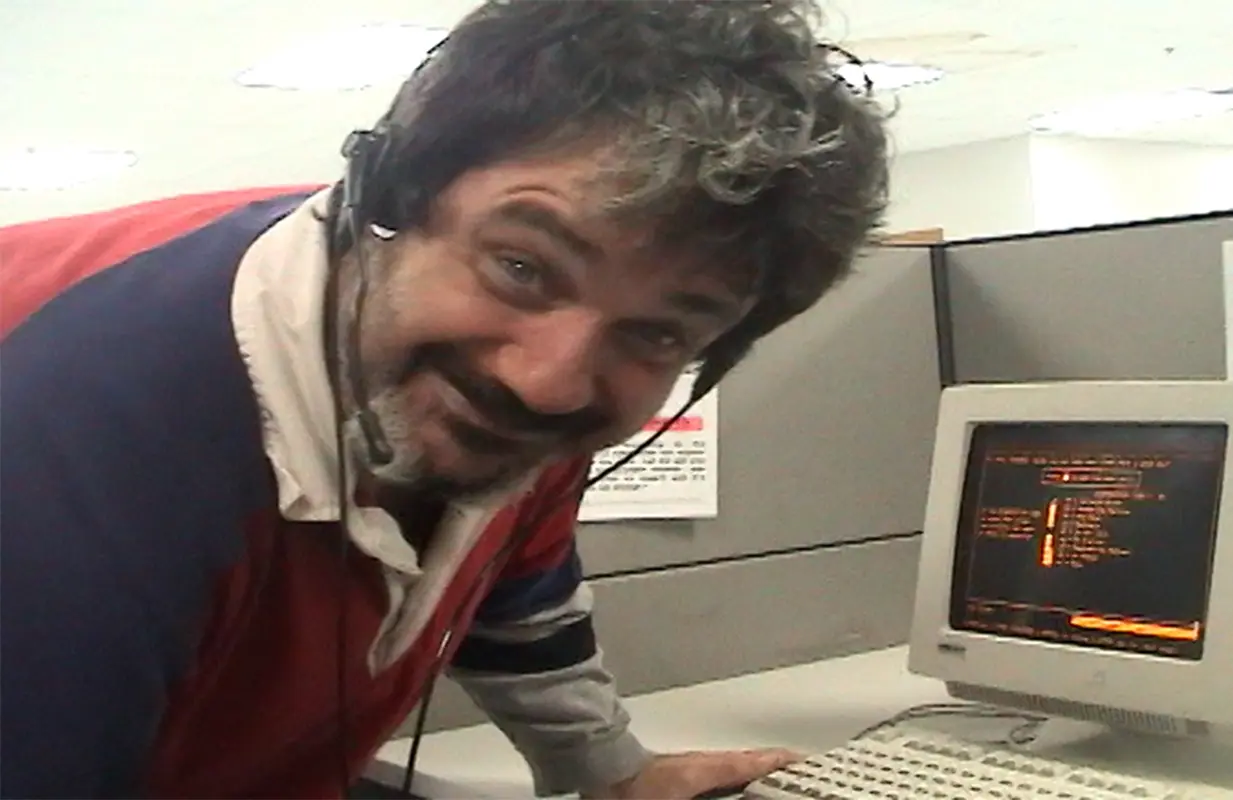

Pat Pespas at the Civic Development Group call center in the early 2000s (Photo: HBO)

Pat Pespas at the Civic Development Group call center in the early 2000s (Photo: HBO)If there's a golden rule in telemarketing, it's that it never hurts to ask — or, as a manager tells top salesman Pat Pespas, "Just keep pushing." That mantra was burned into the brains of the callers at Civic Development Group, the company at the center of HBO's Telemarketers. Reminders about sticking to the script littered the office, as did signs detailing the appropriate rebuttals to concerns from people on the other end of the line. "Your house just burned down, John? Is it completely totaled?" asks one caller in early-aughts footage filmed by fellow employee Sam Lipman-Stern, who co-directed the docuseries with Adam Bhala Lough. "Now John, I don't want to burn you, but we do have a bronze [donation package] at $20, or a booster at $15."

In the years that followed, Lipman-Stern and Pespas harnessed the lessons they learned at CDG and put them to good use as amateur sleuths investigating the company, and later, the predatory practices underpinning the entire telemarketing industry. For nearly two decades, they followed Pespas' belief that they were involved in "a big bullsh*t scam" wherever it led them. The two left no stone unturned in their quest for the truth, and when they uncovered an even larger conspiracy, they kept going, taking their findings to the U.S. Senate in hopes of enacting change on a federal level.

The Telemarketers co-director and narrator wasn't always so committed to asking hard-hitting questions. Lipman-Stern, who was hired by CDG after dropping out of high school, explains he was told he was raising money for charitable police groups like the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP). Though he was aware his company kept 90% of each donation — a detail he was required to disclose to curious potential donors — he "didn't think [he] was doing anything bad," he admits.

It wasn't until Pespas voiced concerns about the "shady sh*t going on" that they began taking a closer look at the business model. Episode 1 lays out how the company's tactics evolved from the 1990s to the late 2000s, when CDG expanded its national footprint and rebranded to create the impression that these new offices were directly connected to law enforcement groups. (Lipman-Stern and Pespas' call center became the "New Jersey FOP Fundraising Center," for example.) Under this new "consultant model," employees no longer had to say they were calling "on behalf of" charitable organizations; they could now pretend they were law enforcement officers seeking donations, a ruse that increased profits exponentially.

In 2009 — shortly after Lipman-Stern was fired for filming office antics and uploading them online — the Federal Trade Commission uncovered evidence of CDG's fraud and shut down the entire operation. Lipman-Stern and Pespas' investigation could have stopped there, as the scam they sought to expose was now out in the open, but they weren't satisfied. The unlikely friends sensed that owners Scott Pasch and David Keezer, who were fined $18.8 million for orchestrating the telemarketing scheme, were just the tip of the iceberg, and when they learned that similar companies had emerged in the wake of CDG's downfall, they set out to "take down the entire industry" from the inside.

What began as short YouTube videos memorializing the dysfunction at the call center thus transformed into a legitimate investigative documentary. Though Lipman-Stern and Pespas were short on resources — they worked out of a McDonald's with reliable Wi-Fi and filmed on low-resolution camcorders — they let their journalistic instincts guide them and followed up on every lead. The duo cold-called organizations they used to "represent" during their CDG days and dug into these so-called charities, discovering rampant corruption and a lack of government oversight. In time, they hired a film crew and interviewed "anybody that was willing to talk," including someone at the Better Business Bureau and the owner of a different telemarketing company who claims law enforcement officers are running their own grift, but requested anonymity for fear of retaliation.

As Lipman-Stern and Pespas dove deeper into the FOP, they became convinced they were being followed by undercover officers, but they pressed on, interviewing "Badge Fraud" whistleblower Reverend James Trankle and John Hulse, a member of the New Jersey Policemen's Benevolent Association. (The PBA, considered a rival of the FOP, stopped using telemarketers in the 1990s.) The sleuths' tenacity paid off: Trankle provided proof that the FOP actively encouraged officers to work at the "NJ FOP Fundraising Center," even as the union publicly distanced itself from CDG's deceptive practices.

Lipman-Stern found more damning evidence when he looked into the FTC's case files from 2009, which revealed the "consultant model" originated with the FOP, which allegedly threatened to fire CDG if they didn't go along with the scheme. "Behind these deceptive scripts, there were state FOPs signing off on the language," he explains via voiceover, adding that the unions would "pitch old stories of dead cops" to mention on calls. "I couldn't understand how anybody could look at this and think CDG had acted alone."

At the end of Episode 2, the investigation comes to a sudden halt when Pespas, who struggled with addiction throughout his friendship with Lipman-Stern, disappears. It takes nearly a decade for them to resume their work, but when they finally do, they resolve to hold organizations like the FOP accountable for their part in what's become a billion-dollar scam. Once again, they find success simply by asking the right questions. When David Vladeck, the former FTC director who investigated CDG, defends his decision not to go after the police union, Lipman-Stern presses him on the evidence presented in his own case files, and Vladeck fails to offer a cogent rebuttal. It's only after a frustrated Pespas asks, "Why can't the government just stop this?" that Vladeck engages with the substance of their argument: "Because police unions are incredibly powerful," he says. "Who wants to be on the other side of the Fraternal Order of Police?"

Later, Pespas goes undercover at another telemarketing firm, and he learns an astounding amount of information just by playing dumb. His manager explains that the latest iteration of the scheme involves political action committees (PACs), as employees aren't required to disclose how much money goes to the cause itself — or even that they're paid callers. "Why the switch? What is the difference?" Pespas asks of the transition from calling on behalf of charities to PACs. "Well, who makes the rules?" his manager says. "Politicians make the rules. They make it easier for political action committees."

Pespas may have an impressive ability to get incriminating information out of his manager, but he's by no means a professional investigator — that much becomes clear when he repeatedly mispronounces the name of the National FOP president, blowing his one chance at an interview. Still, Telemarketers stands as a testament to all that can be accomplished by those willing to ask the tough questions, regardless of their inexperience or limited resources. The HBO docuseries succeeds precisely because Lipman-Stern and Pespas never lost sight of the directive to "just keep pushing," a mentality CDG bosses likely couldn't have imagined would one day be used against them so effectively.

Telemarketers is streaming on Max.

Claire Spellberg Lustig is the Senior Editor at Primetimer and a scholar of The View. Follow her on Twitter at @c_spellberg.

TOPICS: Telemarketers, HBO, Adam Bhala Lough, Pat Pespas, Sam Lipman-Stern