The Congress Is the Ken Burns Film We Need Today

-

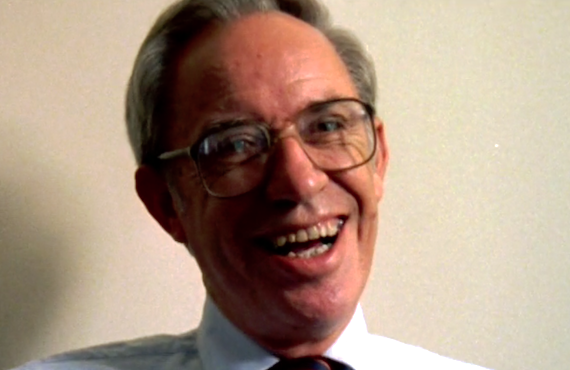

Ken Burns turned his documentary camera on The Congress in 1988. (Photo: MasterClass)

Ken Burns turned his documentary camera on The Congress in 1988. (Photo: MasterClass)The Congress

1988

Watch on: Amazon Prime Video | YouTubeKen Burns isn't exactly an overlooked filmmaker. At the peak of his fame in the 1990s, General Motors — at the time the world’s largest company — wrote him a huge check every year to spend as he pleased. Even now his multi-night documentaries are promoted for months and are rebroadcast constantly on PBS stations.

This Fourth of July, though, I’m recommending a Ken Burns classic you’ve almost certainly never seen. Actually, it aired so long ago and the subject was so banal and uncontroversial at the time that, even if you did sit through The Congress, under congressional oath you’d probably deny ever having done such a thing.

The Congress is more than an entertaining film about the branch of government that gets little respect outside of C-SPAN. Burns treats the U.S. Congress as though it matters. He celebrates the idea that to get the people’s business done, elected representatives must come together and … um … what’s the word? Compost? Compute? Compromise, that’s it!

Compromise, the grease that turns the wheels of government, is seen today as quaint, archaic, even dangerous. But ask yourself, who was it that declared America’s independence from Great Britain on July 4, 1776? George Washington? Tom Jefferson? The guy with the fancy signature? Few people would guess that it was the Congress that drafted the Declaration of Independence — specifically, the Continental Congress that served from 1775 to 1789, when they were replaced by the U.S. Congress, in accordance with the constitution that they also wrote.

In The Congress you see all of the signature Burns innovations, including the rotoscoping of old photographs that eventually became an iMovie tool named for him. That, and the mellifluous quotes read by voice actors, are his most obvious contributions to documentary filmmaking. (In The Congress you’ll hear lines read by Kurt Vonnegut, Julie Harris, Derek Jacobi, singer Ronnie Gilbert, and a Burns favorite, Garrison Keillor.)

But Burns also popularized the raconteur-explainer, a talking head who charms viewers with folksy yarns that the director uses to push his agenda. An example of this in The Congress is when newspaperman Charley McDowell tells the story of George Washington’s first visit to the Capitol. The president has negotiated and signed a treaty, and he has personally delivered it to the Senate, then located in New York, for that body’s approval per the new constitution. Washington — who has never had to ask a favor of Congress — is expecting the treaty to be ratified while he waits in the lobby.

Finally, says McDowell, “the Senate told him that they believed it would take till tomorrow or maybe another day.” The president orders his carriage and rides off in a huff, “and he never returned to the Capitol.” But then comes the moral of the story: “They ratified a treaty by arguing about it and making a little change somewhere,” says McDowell. “And the government was operating.”

The Congress was released in 1988, one year before Burns exploded on the scene with his nine-night extravaganza about the Yanks and the Rebs. After The Civil War — still the most-watched PBS series of all time — Burns never made another regular-sized film again. (One, about the forgotten heavyweight champion Jack Johnson, Unforgiveable Blackness, was 214 minutes long.)

At just 86 minutes plus credits, The Congress is a study in compression and pacing, covering two centuries of Congress’ greatest hits — the debates over westward expansion, fights over slavery (which occasionally got physical), the Reconstruction era, the Gilded Age, the McCarthy years, civil rights, Vietnam, Watergate — in the film’s first hour, then spending the balance of its time asking what it all means.

Burns amuses us with stories of Congress at its liveliest and most dramatic, with snapshots of some of the individuals who shaped the institution over the decades: Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, Thomas Brackett Read, Everett Dirksen, and Sam Rayburn. Using colorful quotes, archival footage, and compelling images from his own camera crew, Burns makes the point that Congress has never been anything less than chaotic, contentious, and — until lately, anyway — consequential.

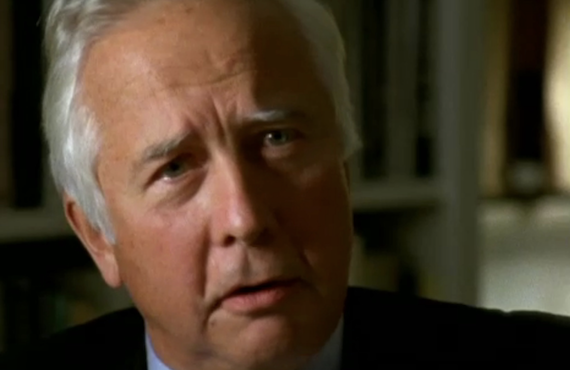

As in previous films, Burns uses David McCullough as both narrator and talking head in The Congress. I never understood this. Granted, McCullough is a raconteur-explainer par excellence and was blessed with a golden throat. But having him move from one side of the curtain to the other produces decidedly odd results. In one sequence in The Congress, narrator McCullough is describing the resolution debated by the House in 1910 that would curtail the Speaker’s power. “After 29 hours of debate, the resolution carried,” the stentorian voice tells us. “The iron rule of Speaker Cannon was ended.”

Thirty seconds later, though, McCullough is on screen offering his perspective on the end of Speaker Cannon’s iron rule. “It was an extremely important change in our country,” he says. It’s like Lester Holt stopping the presidential debate to offer analysis. You do one or the other. (Burns finally came to his senses and moved McCullough behind the curtain for The Civil War.)

The last half hour of the film is unlike the rest, and is especially fitting to watch on July Fourth, as it's a meditation on why we need Congress. The idea that legislators have too much power is an old one; as the George Washington story suggests, the executive often wishes that Congress would just get out of the way.

Burns uses his most thoughtful experts to push back strongly against that narrative, which in 1988 was just starting to gain momentum. (In that year, a former Kansas City talk jock named Rush Limbaugh went coast to coast.) The most forceful rebuttal comes from Barbara Fields, the future MacArthur fellow and first black woman to make tenure at Columbia University. Even while making The Congress, Burns was busy with The Civil War, in which Fields would shine, coolly contradicting everything that came out of the mouth of that film’s Southern-sympathizing ranconteur-explainer, Shelby Foote.

Fields is well aware that Congress has let African-Americans down, in painful fashion, again and again over the course of 200 years. But when she hears white critics say that “democracy is a pain in the neck, which of course it is,” she bristles. Her response seems prophetic today. Denouncing Congress just for being Congress, says Fields, “is a criticism of the whole idea of a government by as well as for the people. And that is a criticism of democracy. I wonder whether the ideal of democracy lives in a real sense in our country today.”

Aaron Barnhart has written about television since 1994, including 15 years as TV critic for the Kansas City Star.

TOPICS: Ken Burns, ABC Family, PBS, David McCullough