On Netflix’s Confession Tapes, the Camera Never Blinks, But Justice Does

-

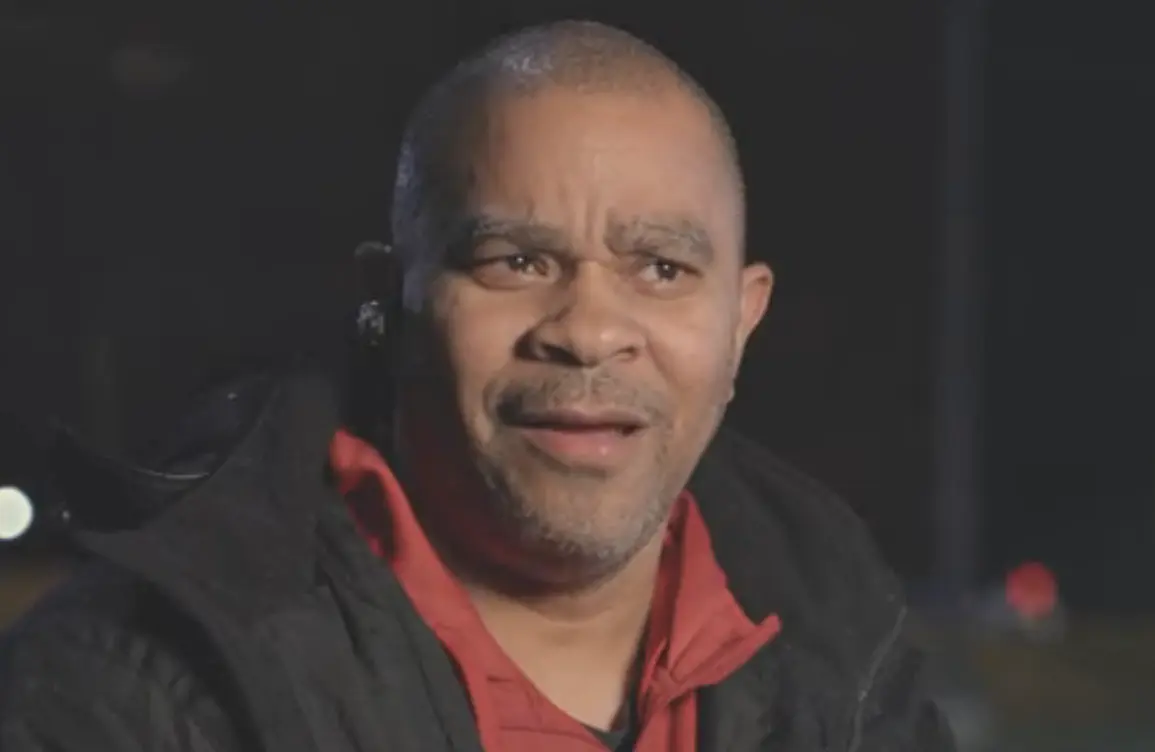

Calvin Alston spent nearly 21 years in prison for the 1984 murder of Catherine Fuller, but in The Confession Tapes he describes being coerced into falsely implicating himself and thirteen other young men. Six of them remain in prison to this day. (Photo: Meena Singh/Netflix)

Calvin Alston spent nearly 21 years in prison for the 1984 murder of Catherine Fuller, but in The Confession Tapes he describes being coerced into falsely implicating himself and thirteen other young men. Six of them remain in prison to this day. (Photo: Meena Singh/Netflix)The Confession Tapes (Season 1)

Watch on Netflix

Season 2 drops June 21At the heart of the spellbinding Netflix series The Confession Tapes rests a troubling question: Would we rather be told a comforting lie than a hard truth? It's a question that's been amplified recently thanks to Ava DuVernay's gut-wrenching Netflix miniseries, When They See Us.

When people are the victims of violent crimes, the survivors (and often the public) want answers. More than that, they want closure. And there is no quicker path to closure than a videotaped confession from the accused. Netflix's documentary series The Confession Tapes examines cases in which people claim they were convicted of murder based on false or coerced on-camera admissions of guilt, and as seen with the "exonerated five" at the center of DuVernay's When They See Us, those confessions are about as reliable as polygraph tests, voice analysis, and other supposedly incorruptible forms of evidence. Which is to say, not nearly as reliable as you may think. Confessions come burbling out of people after hours of interrogation, threats, flattery, and trickery at the hands of supposed upholders of the law.

In the two-part opener of Season 1, three young men were convicted of murder in Washington State after Canadian law enforcement officers pulled one of them into an elaborate trap, preying on his need for approval and easy money. Though the technique is illegal in the U.S., the hidden-camera video was ruled admissible, and just like that, three lives were ruined.

“There are many people who would say, ‘Oh, I wouldn’t confess to something I didn’t do.’ That’s not true," says post-conviction counselor John Blume, in one episode. "Almost anyone can under the right circumstances.”

I knew there was a whole innocence industry out there — and why wouldn’t there be, with an estimated 100,000 wrongfully convicted Americans behind bars — but The Confession Tapes introduced me to the post-conviction counselor, the false-confessions expert, and the wrongful-conviction attorney. Director Kelly Loudenberg even found an expert who has studied the trap that the Mounties set for those three innocents.

Together with evidence and the contributions of journalists and defense attorneys, The Confession Tapes assembles a damning case against letting videotaped confessions anywhere near a courtroom. The series has a point of view, but you hardly notice it since Loudenberg only needs to recount the facts of these judicial travesties. Remarkably, she even persuaded some DAs and detectives to go on camera and defend their indefensible cases.

In the case of the Canadian sting operation, the lead detective was approached by the FBI with a highly credible tip, one that would very likely have led him to the real killers, but since that would have forced him to drop his case against the three innocents, he ignored the FBI’s tip. Pressed by Loudenberg, he said, “You can always look at other outside things but it always comes back to...” the guys he’s decided are guilty.

Why do police, courts, and the news media continue perpetuating the lie that confessions are golden? Because, as they well know, it gives communities closure. It makes them look like heroes. The drama Rectify did a good job showing how deeply we get invested in the guilt of a person, even as proof of their innocence stacks up.

“Departments are judged on their crime rates,” one expert tells Loudenberg. “If you have a high homicide rate, you need to bring it down and you need to show a high closure rate. Pressure’s on, you want to close it, and you want to close it quick.”

Just as important, a videotaped confession gives a news story an ending. I’m embarrassed to say that for 15 years covering the media, I didn’t realize how complicit journalism was in this whole enterprise, but it’s the narrative that fuels these cases. People are drawn to crime stories, the bloodier the better — but you’d better have a solid ending. “I didn’t get closure from last night’s SVU,” said no one ever. “We’ll stay on this story for you,” said every local TV anchor everywhere.

Many years ago, I reviewed Capturing the Friedmans, Andrew Jarecki’s Oscar-nominated film, which examined the complicated relationship between the New York news media and the NYPD as they worked to prosecute an accused father and son using the two mens' confessions as evidence against them. But New York is a huge, ravenous media market, I told myself, surely things like that didn’t happen in small-town America.

How wrong I was. Four of the six cases featured in Season 1 of The Confession Tapes involve tiny police departments reacting to violent crimes they rarely if ever see, and the juries in these towns tend to give law enforcement the benefit of the doubt. It’s a recipe for quick closure at any cost.

The Confession Tapes is one of several projects on the fallibility of our criminal system that Loudenberg is developing for Netflix, nicely complementing the higher-visibility work of Ava DuVernay. Indeed, one of the cases in Season 1, from 1980s Washington, D.C., has uncanny parallels to the Central Park jogger case that DuVernay explores in When They See Us.

Like so many things in Netflix World, The Confession Tapes does not play by the rules. The cases Loudenberg chose for Season 1 do not have closure. From what I can tell, the people whose lives were ruined by faulty confessions are all still rotting in prison. Most have exhausted their appeals, and could only be freed by the governor or the president.

The Confession Tapes undermines the crime-TV genre in every way, from how it tells its stories, to how it forces us to wrestle with deeply-ingrained beliefs about criminal justice that have been reinforced for us through a lifetime of television.

But is one powerful TV series enough to change all that? As I explored in my review of Casting JonBenet, it's very hard to move people off of strongly-held opinions — and as we know, people get surprisingly passionate about a lot of things. Like the mother of four young children killed when her husband drives the family car into a lake in the concluding episode of Season 1. A reporter asks a woman-on-the-street what she thinks of the mother. “She’s a bitch,” says the woman. Why? Because “she didn’t show any emotion,” at least not on camera, and does any other emotion count?

At the end of one of the saddest episodes of The Confession Tapes, about a young man from rural Georgia — a state that does not allow experts on video confessions to testify for the defense — the man’s attorney sighs, “A lot of judges like to tell jurors that we have the best criminal justice system in the world. Maybe we do. But at the end of the day it’s only as good as law enforcement is fair, as the defense lawyer is skilled, as the jurors are open-minded, and the experts and the testimony you are allowed to put up. And even then it’s a human endeavor.”

Aaron Barnhart has written about television since 1994, including 15 years as TV critic for the Kansas City Star.

TOPICS: Netflix, The Confession Tapes, When They See Us, Ava DuVernay, Kelly Loudenberg, Documentaries

- Physical: Asia: Team Mongolia's Enkh-Orgil Baatarkhuu shares what drove him to join, reflects on his experience, and more

- Physical: Asia: Team Mongolia's Orkhonbayar Bayarsaikhan explores selection, team effort, and the show’s significance

- "That's the beauty of this tournament" - Physical: Asia Team Japan's Yushin Okami praises Mongolia’s remarkable strength and unity

- "Warriors on their horses!" - Physical: Asia’s Dulguun Enkhbat appreciates supporters as the team brings Mongolian spirit to the world