Myth of the Zodiac Killer Director Believes His Doc 'Blows Apart' the Unsolved Murders

-

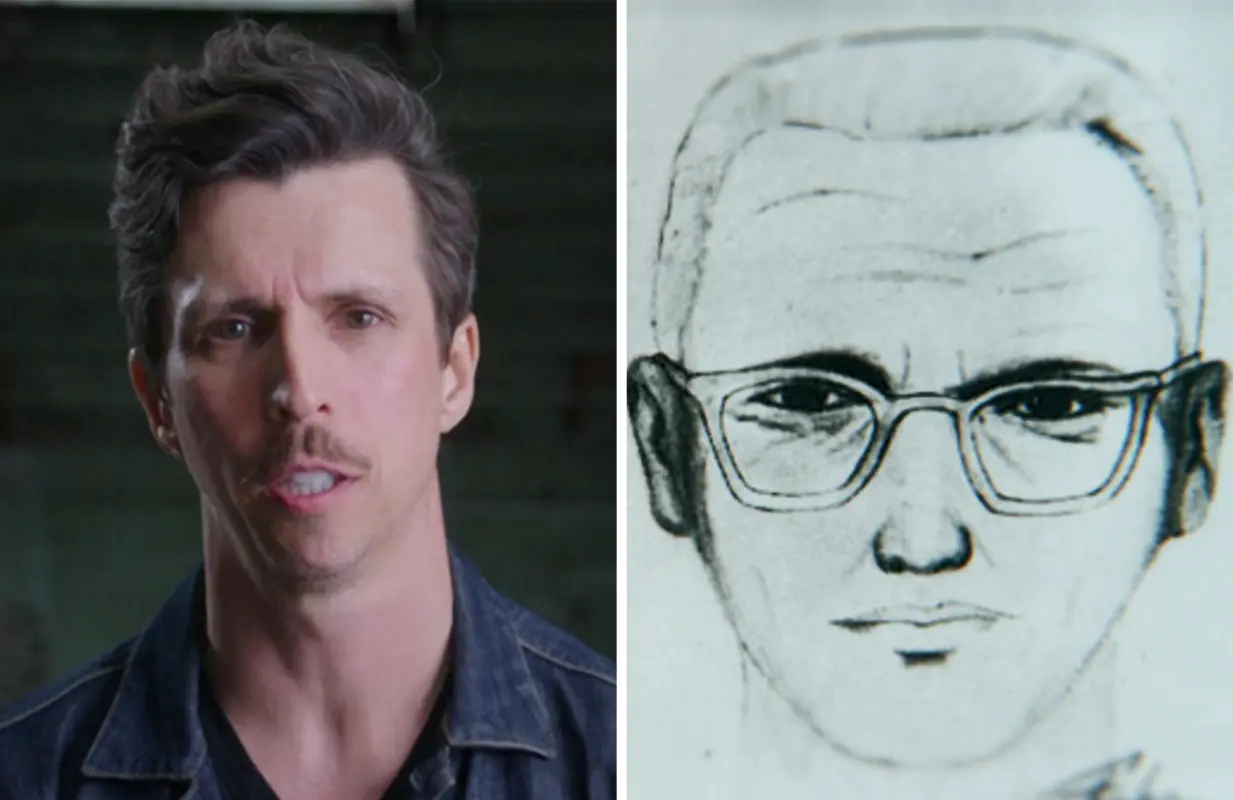

Myth of the Zodiac Killer director Andrew Nock casts doubt on the existence of the Zodiac Killer in his new documentary. (Photos: Peacock)

Myth of the Zodiac Killer director Andrew Nock casts doubt on the existence of the Zodiac Killer in his new documentary. (Photos: Peacock)For the thousands of online sleuths devoted to cracking the Zodiac Killer case, Peacock's latest true-crime series is downright blasphemous. Based on a theory put forth by academic Thomas Henry Horan, Myth of the Zodiac Killer views the infamous unsolved murders and the corresponding cyphers and letters with a heavy dose of skepticism. Unlike the legions of detectives (of both the legitimate and armchair variety) who believe a single man murdered five people in the San Francisco Bay Area between December 1968 and October 1969, Horan posits that the crimes were unrelated, and, as such, "the Zodiac Killer is a fictional character."

Over the course of the two-part documentary, Horan lays out his theory, offering what he believes is compelling evidence pointing to a "Zodiac hoax." He identifies key differences between the murders — including the choice of weapon and the disguise worn by the killer in the September 1969 stabbing at Lake Berryessa — that complicate the prevailing narrative about a single perpetrator, and he raises questions about why potential suspects, like Jim Phillips Crabtree, the ex-husband of victim Darlene Ferrin, were cleared by investigators. Horan also disputes the authenticity of the dozens of letters sent to local newspapers in the 1960s and 1970s, as well as the phone calls in which an unknown man claimed responsibility for the first two attacks.

While Myth of the Zodiac Killer director Andrew Nock admits many of Horan's ideas are "crazy," he found himself swayed by the controversial professor and his hypothesis. Beyond interviewing the victims' family members and detectives involved in the investigation, Nock, who's known for his work on paranormal docuseries like Unidentified With Demi Lovato, plays an active role in the film: He visits many of the crime scenes, narrates each episode, and even sends the letters to a team of computational linguists, who use stylometry to unearth clues about their author (or authors, as Horan and Nock believe). By the time the screen fades to black, Nock is convinced that the Zodiac Killer doesn't exist — or at the very least, he harbors serious doubts that "a single person committed all four of these horrible crimes," as he says in the documentary's closing minutes.

In a lengthy conversation with Primetimer, Nock explains why he believes Myth of the Zodiac Killer "blows apart the whole lone serial killer, supervillain, criminal mastermind theory," discusses the parts of Horan's theory he found most (and least) convincing, and breaks down his off-putting interview with Jim Phillips Crabtree.

The Zodiac murders are probably the most famous unsolved case in the U.S. What drew you to this case? Were you already researching a potential documentary about these murders when you encountered Thomas Horan's theory online?

It's something that so many people have dug into, and I think that's the reason why it really drew me in as a filmmaker. There are thousands and thousands of people online, all over the world, who study this case because it's quite unusual for an unsolved case that there are thousands of pages available to read of the police reports. And so it's made thousands of people into so-called experts, and they're all online arguing with each other. There's so many different suspects that people will live and die by, like, "This is the Zodiac Killer. This is the criminal mastermind, the supervillain that's evaded justice for over 50 years." That's what really drew me to doing this documentary because I just couldn't believe how many people — and how angry they are at each other. They're really just like, "You're stupid! He couldn't be this person."

And then there was this one character in the middle of all this that they all disliked, which was strange and very appealing to me. It was this professor from the Midwest who had this crazy theory — a really controversial theory in the Zodiac community — that there was no Zodiac. That's what really sparked my interest in this case.

What was your initial reaction to Horan's theory?

My gut reaction was, "How could everyone have got it so wrong?" The authorities, the FBI, multiple police agencies, thousands of people online — how did they all have it so wrong? Most people's knowledge comes from the Robert Graysmith book from the '80s or the David Fincher movie, and that has a very particular point of view as to the crimes and the theory that there was one killer, and one killer in particular [Arthur Leigh Allen], who has been cleared many, many times. So that was really my take: That it must be one guy because that's what we've been told. And interestingly enough, when I started talking to family members of the victims, they said the same thing. They said, "Well, once the police put [forth] the idea that it was the Zodiac, that's what you believed." And that's what they believed for 50 years.

When you look at the police reports, when you look at the reporting on these crimes, they absolutely had other suspects of these different crimes. But because a suspect for one of the Zodiac crimes wasn't present for one of the other so-called Zodiac crimes, they were dismissed.

In the film, Horan walks you through evidence that he believes supports his Zodiac hoax theory. Of the evidence presented, what did you find the most convincing? And on the flip side, was there anything you were skeptical about or pressed him on further?

Yes [laughs]. He had a lot of different crazy, wild ideas, and a lot of them, he never really put into practice. He hadn't spoken to a lot of these people or gone to a lot of these places. That's what I wanted to do, be boots on the ground and put these theories that he had gotten from reading police reports and comparing evidence — I wanted to put it into practice.

I think the most compelling was when we both went to Lake Herman Road, the site of the first so-called Zodiac crime, and we measured out the bullet casings that the police had done back in 1968. We had the original police reports and the sketches and the measurements, and we measured things out exactly, and it did tell us a story. We know there were two cars in the pullout at one point because there was an eyewitness who drove past. And if you measure this one lone 22-caliber casing that's 20 feet away from the vehicle that David [Faraday] and Betty Lou [Jensen] were killed in, the only way someone could have fired a 22-caliber pistol — and the casing doesn't fly that far – was if the person had gotten out the passenger seat of the murder vehicle. And if someone's in the passenger seat, then someone else must be driving. That was the first moment I was like, "Wow, this isn't a lone wolf. This isn't some crazy guy, a serial killer. There must have been two people at this one crime." So, it kind of blows apart the whole lone serial killer, supervillain, criminal mastermind theory.

On the flip side, the San Francisco crime where Paul Stine [was] murdered — the taxi driver — what's strange is that's the only case that we know of, a so-called Zodiac murder, where the killer took a trophy. We don't know of any other trophies that were taken from any of the other crime scenes, but he did take part of [Stine's] shirt, and then someone mailed in letters to the San Francisco Chronicle and attorney Melvin Belli. [Horan] didn't really have a great theory as to how that happened. He was saying that the evidence room at San Francisco PD was easily accessible to journalists, for example, and when I talked to Detective [Frank] Falzon from San Francisco PD, he said, "That's not true at all. There's no way someone could rip off a piece of evidence and walk out." That was the only one that was a bit of a mystery to me as to how that could've happened.

There were other examples [like] the famous phone calls. For the first crime, I spoke to a local photographer who had a short-wave radio; he heard the report of the bodies at Lake Herman Road. That's how he went there to take photographs.

Blue Rock Springs, I spoke to a guy, who's not in the documentary, who heard a report over his short-wave radio. Someone could've written those details down and written a letter, the first letter that came in. So there were ways that someone not involved in the crime could've gotten access to information and written those letters. And I think the letters have really distracted the police from solving these individual crimes. Because it's really the letters that link these crimes together.

Did you and Thomas discuss the possibility that the killer was alone, walked around to the passenger side of the car to get a weapon from the glove compartment, and then fired over the car?

If you look at the eyewitness reports, the timings are very interesting. There was very, very little time between [when] this guy James Owen drove past the two cars in the pullout, and then the lady drove past and saw the bodies on the ground. It was only a few minutes; there was not a lot of time. So it's hard to believe that someone was kind of futzing around, moving from one side of the car to the other, with these two teenagers who were probably terrified in there and would've ran. It feels like, based on the eyewitness evidence, that this must have happened extremely quickly.

Jim Phillips Crabtree, the ex-husband of victim Darlene Ferrin, has largely avoided the public eye in the decades since the 1969 murder. How did you convince him to participate in the documentary?

That's a great question — I should be careful what I say, only because most people believed he was dead. You could basically look at this man's life and write a history of the 1960s. I mean, he went through everything in the '60s: Haight-Ashbury, hippie communes, he joined a cult, he was a cryptographer in the Army. He made other really wild claims that didn't make it into the show that I should probably not share.

But basically, I just said to him, "We don't think these crimes are related." Because people thought he was the Zodiac at one point. I mean, he was a cryptographer in the military; he was married to one of the victims; he was brought in for questioning after the Paul Stine murder, which is interesting. I just said to him, "Look, this is a chance for you to clear your name." And he said, "Oh, okay. I want to go there and set the record straight." And then in the interview he told me he wanted to "set it on fire," so that's what he did.

Crabtree denies killing Ferrin, but his testimony was concerning, to put it mildly. What was your impression of Crabtree when you met with him? Did he strike you as a reliable narrator?

Well, yes he does. I mean, I believe him — I don't think Jim is the Zodiac Killer. But he likes to tease with things. When he said he was taking an acid trip on the day Darlene was killed, I said, "Was that your alibi?" and he said, "That was one of them."

If you read the original police report, he was with his common-law wife taking a hike in Boulder Creek, California, and he told me it was backed up by– he saw a judge and he waved at the judge, and there were people playing music around a campfire. I haven't found any documentation that a judge saw him in any of the police reports. And the other thing he said was he had a rickety old pick-up truck that couldn't have made it to Vallejo. So, I think he could have set people's minds at ease a little bit better with a better retelling of the story.

Why do you think he went out of his way to "fuel the fire of speculation" that he's the Zodiac Killer, as you say in the docuseries?

Because I think he's litigious [laughs]. He's told me that — he likes to kneecap people.

You know, he's a very interesting guy. He tells me he's a pacifist, but he didn't have very good things to say about Darlene. I was quite taken aback. He was married to her such a long time ago, and I know he feels that Darlene's family feels he had something to do with the crime.

But there's interesting things, like in the police reports — Darlene's older sister said that at the funeral, Jim was there and sat in the back row. But Jim was like, "I was never there at the funeral," and when I spoke to Darlene's younger sister, Kris, she told me there was never a funeral. Her older sisters are just as unreliable as other people, because they made up crazy stories, too. They had said some unreliable things, especially on [shows] like Geraldo back in the '80s and '90s, so I wanted to talk to the younger sister who had never been on camera before, never told her story, because it felt that she was far more reliable and level-headed about the events. And she was actually there in Vallejo when it happened, whereas the older sisters had already left home.

She remembers Jim being a very strange character. The family weren't too thrilled with him because he took their girl away and traveled all across America, the Virgin Islands — he was always going on these strange trips. And even today, he tells me he's got nine kids from six different women and he's always on the move. He's a very interesting man — that's what I'll say about Jim.

So much of the evidence in these murders is circumstantial, which you acknowledge towards the end of the film. Did the absence of hard facts change your process as a documentarian?

Yes and no. I was really just fascinated by Thomas' theory and wanted to try and put that into practice, and as we've discussed, some of it made sense, and some of it didn't. The fact that no one's been able to solve this crime for over 50 years now makes me feel like they've been looking at it the wrong way. My feeling is that the authorities, who still have these as open cases, are still thinking of this in a way where it has to be one person responsible for the cyphers, and the cyphers have told us nothing. And they've all been deciphered now other than two very, very short ones which I'm told are impossible [to crack] by the experts, and they've told us nothing really. The letters have told us nothing.

The letters almost seem irrelevant to these murders now.

Except the authorities didn't take them seriously to begin with, but when they kept coming, they thought, "Well, it must be the person who wrote these letters who committed these crimes." And that's what we wanted to show with the A.I. analysis that the professors at the Sorbonne did with this technique called computational linguistics — to really analyze these letters in a way they've never been analyzed before. People have studied the handwriting for years, and that didn't really tell us anything. But it's really hard to disguise the way you write sentences, I'm told. You can try and disguise your style of writing but it's something that's ingrained in the way everybody writes that you can really tell if one person has written a bunch of the letters or not.

That's really what I thought was interesting because if we could show that these letters were not written by one author, that could push forward this idea that there wasn't one person responsible for the crimes either. And I think that's something that the friends and the families of the victims would like because they would like these crimes solved, obviously, and they've never claimed any adjustments. That's maybe because everyone has had a blinkered view of this crime.

Since completing the documentary, have you spoken to anyone who said they're now going to take a different approach to investigating the murders? I imagine it's a cold case; there can't be many detectives actively working on it in 2023.

It's very hard to tell because we talked to Benicia PD, Vallejo PD, Napa County Sheriff's, San Francisco PD, and they're all very tight-lipped. But they did say they're consistently bombarded with armchair theorists, with their ideas, and it's kind of stopped them from really digging into the case anymore. Because they obviously have their own pressing cases, other cold cases.

But it was interesting — in a scene that didn't make it into the documentary, I got together with a lot of detectives from San Francisco in the 1970s. They all have breakfast at the same diner every week, including Frank Falzon; he's kind of like the ringleader of these guys who have incredible stories. But the Zodiac only committed one murder in San Francisco, so to them it wasn't a huge case. I mean, when the letters started coming in making terrorist threats against kids on school buses, it was a big deal, but they had multiple murders every day in San Francisco in the late '60s–early '70s. They had the Zebra murders — they had a lot going on. So to them it was just one murder. It was an important murder, but they had robberies of cab drivers every day. So what they said to me was, they just couldn't focus all their attention and their resources on this one case, even though the media made it into a huge deal.

It's interesting because that's what we saw with the Golden State Killer — all these different jurisdictions that were not communicating effectively, and as a result, he wasn't captured for 50 years.

Yeah, they told me that there was communication between the different police departments, but as you can imagine, back in the late '60s, that communication was very primitive. And they all wanted to try and crack this case individually. So it's very hard to know how much they really did share. Frank Falzon — as far as I know — wasn't able, based on his workload, to study what happened in Vallejo, for example. That wasn't his territory, his patch as they say. So he only really had the evidence they had in San Francisco, and Vallejo wasn't studying what happened in San Francisco.

I just think that maybe the only way to crack this case is to look at these cases individually again and look at the suspects they potentially had at the time. There's a lot of evidence that David and Betty Lou were caught up in some kind of drug– I mean, they weren't into drugs. They weren't buying drugs, but David was trying to bust some sort of drug pusher at his high school, and there's evidence to show that. But at the time it was investigated, they just sort of dropped that lead once Darlene was killed. And then when the kids were killed in Lake Berryessa — or Cecelia [Ann Shepard] was — they just started looking at different avenues, at that point.

What do you hope this film adds to the decades of discussion about the Zodiac Killer? Is there something specific you want viewers to take away from the documentary?

I want them to have an open mind [that] these could have been separate crimes. There are different weapons used, different M.O., different victim profiles, different eyewitness reports, different locations, the trophy that was taken in one case and not in the others. Just look at these as separate crimes that were linked together in an era of paranoia. I mean, the late '60s-early '70s, you've got the Sharon Tate murders and Watergate — there was a real distrust of the young people from an older generation. Drugs– it fueled the fire of this kind of generational gap.

And this era of journalism where the Manson murders were on the front page every day for months. The newspapers wanted their own horrible murders, and the Zodiac fed into that. I think the papers really did fuel the fire in this case, and maybe the coverage encouraged people to write fake letters to try and keep it going.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Myth of the Zodiac Killer is now streaming on Peacock.

Claire Spellberg Lustig is the Senior Editor at Primetimer and a scholar of The View. Follow her on Twitter at @c_spellberg.

TOPICS: Myth of the Zodiac Killer, Peacock, Andrew Nock, Jim Phillips Crabtree, Thomas Henry Horan, True Crime