The Velvet Underground Is a Vivid Document of an Art Movement

-

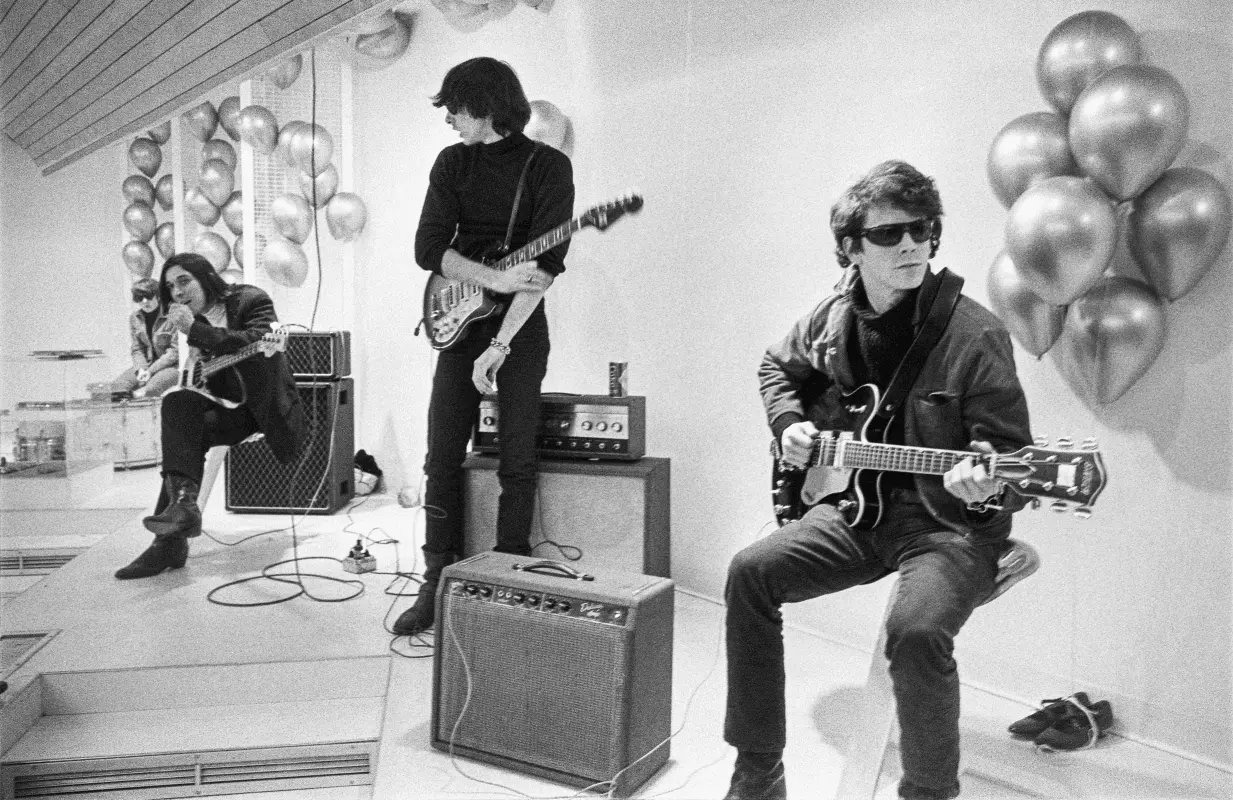

Moe Tucker, John Cale, Sterling Morrison and Lou Reed in an image from The Velvet Underground, premiering Friday on Apple TV+.

Moe Tucker, John Cale, Sterling Morrison and Lou Reed in an image from The Velvet Underground, premiering Friday on Apple TV+.The arc of the traditional rock 'n roll documentary — or the rock biopic, for that matter — is so familiar by now that it may as well be imprinted in our bone marrow. But when it comes to a band like the Velvet Underground and the particular place they hold in our cultural memory, the word "traditional" has no place. They were one of the most influential rock bands of all time, but they're not remembered or revered in the same pantheon as the Beatles or the Rolling Stones or even The Who. They were more aloof, more experimental, more queer. They resisted mythologizing despite having been birthed from an art movement that was so remote and peculiar from everything around it that it may as well have been a myth. The art movement happening in and around Andy Warhol's Factory in 1960s New York City fits less easily into American history narratives than, say, the hippies or the protest movement, but in The Velvet Underground, director Todd Haynes uses the documentary form to create a visceral place and time for his subject to enter the world.

As a cultural touchstone, the Velvet Underground are clearly quite important for Haynes. After seeing the affection he puts on the screen in his new documentary, you understand completely why he titled his 1998 tribute to the glam rock movement of the 1970s Velvet Goldmine. That film featured a main character, played by Ewan McGregor, whose stage persona was patterned largely on Iggy Pop but whose backstory overlaps significantly with the Velvet Underground's Lou Reed, particularly Reed's upbringing, which included electroshock therapy, approved by his parents, to help "cure" him of his homosexuality. This now-legendary aspect of Reed's biography is disputed by his sister, Merrill, one of the many voices Haynes employs to glean a picture of Reed from the people who knew him and were in various ways smitten, frustrated, and despised by him. Reed's death in 2013 means he can't be the voice telling his own story — and Haynes, either by necessity or artistic choice doesn't include much archival footage of Reed speaking at all — but his centrality to the Velvet Underground mythos is present in the ways in which every other talking head in the film recalls him, perpetually unruly and dissatisfied and impossible, but with whom everyone from Warhol to Nico and beyond were in love in some way.

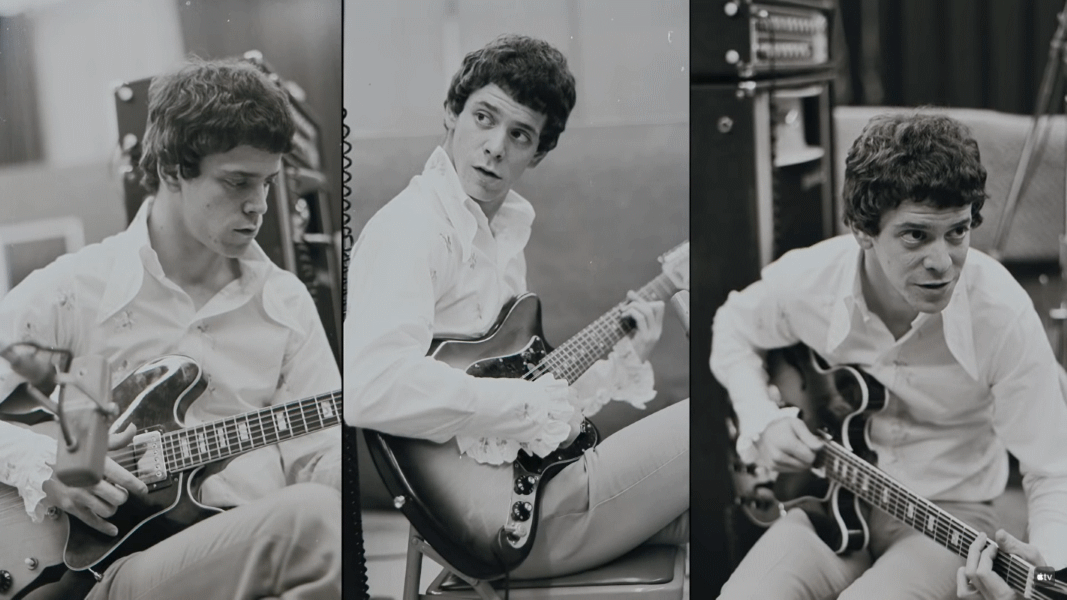

In Reed's absence, the centerpiece of Haynes's documentary becomes John Cale, Reed's musical counterpart whose partnership and sonic experimentations with Reed would ultimately birth the band that would also include guitarist Sterling Morrison and drummer Maureen Tucker. Cale proves to be a phenomenal storyteller; his mellifluous Welsh voice could narrate the next 100 documentaries I see and I'd never tire of it. Cale gets into the nuts and bolts of his and Reed's musical experiments on tracks like "Venus in Furs" and "I'm Waiting for the Man," the way they were making music that nobody at the time was interested in making or, crucially, was even capable of making.

As Cale intelligently and clearly lays out the musical genesis of the band, Haynes gets to the work of populating the kaleidoscope of influences and personalities that made up the New York that Cale and Reed were collaborating in. And that's where The Velvet Underground proves itself to be a true Todd Haynes picture. It's not a bit surprising that Haynes would be able to create such a rich sense of place and time here. He's a master at it in his narrative films: the decadent mod and glam periods in Velvet Goldmine; the Douglas Sirk haze in Far From Heaven; the troubadorian singularity of his Bob Dylan in I'm Not There; the lush romanticism lining the New York city streets in Carol. Wearing the hat of a documentarian, Haynes isn't able to employ costume and art direction in the same way that's previously served him so spectacularly well; instead he manages to use archival footage and the recollections of the people who were there as its own kind of art direction. Of course it helps to have personalities as colorful as musician Jonathan Richman, avant-garde composer La Monte Young, film critic Amy Taubin, actress Mary Woronov, and so many others on hand to fill in their little corner of the mosaic that was the Factory era.

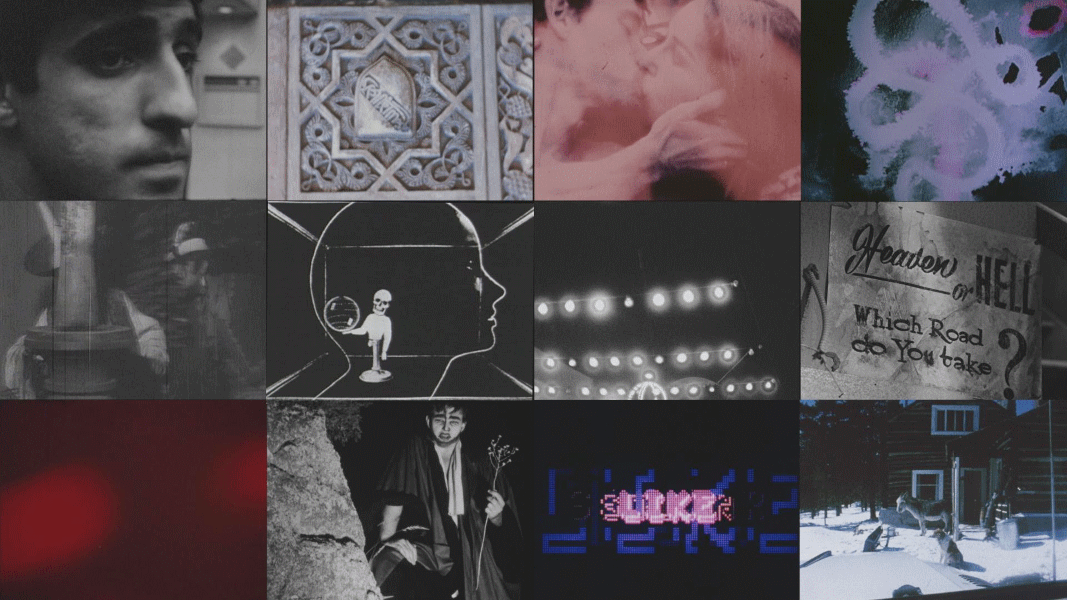

Haynes's fractured visual presentation, where the screen might at any moment be showing three multiple images at a time, conveys how so many disperate elements — Reed, Cale, Tucker, Sterling, Nico, Warhol, New York, art, noise, homosexuality — merged into one cultural moment. Warhol's artist collective has been portrayed in film and TV so often over the years that it's become a kind of stylistic shorthand, but Haynes is dogged in his determination to show the whole picture, to look beyond Andy's mercurial personality and the cliche of the tragically disaffected artiste, to talk about the Factory as a place of creative freedom where people with ungodly talents that didn't have a place in the outside world could have room to create a sound that would inspire generations. The trite quality of that assessment would likely lead almost every participant to roll their eyes, but Haynes has always held on to more than a little romanticism underneath his New Queer Cinema armor.

Not everything fully satisfies, but you get the sense that to Haynes, that's only fitting since Reed and Cale worked together for only a short period of time before the band as it was originally incarnated broke up, ending what Haynes clearly believes was an era unto itself in art, music and culture. The post-Cale years weren't exactly a desert of productivity for The Velvet Underground, but Haynes doesn't seem to have much interest for them, in part because Reed is no longer alive to tell the tale, in part because he seems to be as taken with Cale's telling of the tale as I was, and in part because it's more a movie about a moment in time than it is a biographical account about the rise and fall of one of the great rock bands of our era.

That may be a disapointment for those looking for a more complete portrait. But the evocation of a moment in history here is so strong and the director's approach so at one with his subject that The Velvet Underground succeeds on its own terms. This was a band whose genesis told the story of a movement in American culture that felt both honest and artificial at once, full of posture and noise that nonetheless gave creatures like John Cale and Lou Reed and Nico (and probably more than a few characters from Todd Haynes films) a place to make sense within the American culture. The film turns out to be a goldmine indeed.

The Velvet Underground releases in theaters and on Apple TV+ Friday October 15th.

Joe Reid is the senior writer at Primetimer and co-host of the This Had Oscar Buzz podcast. His work has appeared in Decider, NPR, HuffPost, The Atlantic, Slate, Polygon, Vanity Fair, Vulture, The A.V. Club and more.

TOPICS: The Velvet Underground, Apple TV+, John Cale, Lou Reed, Todd Haynes